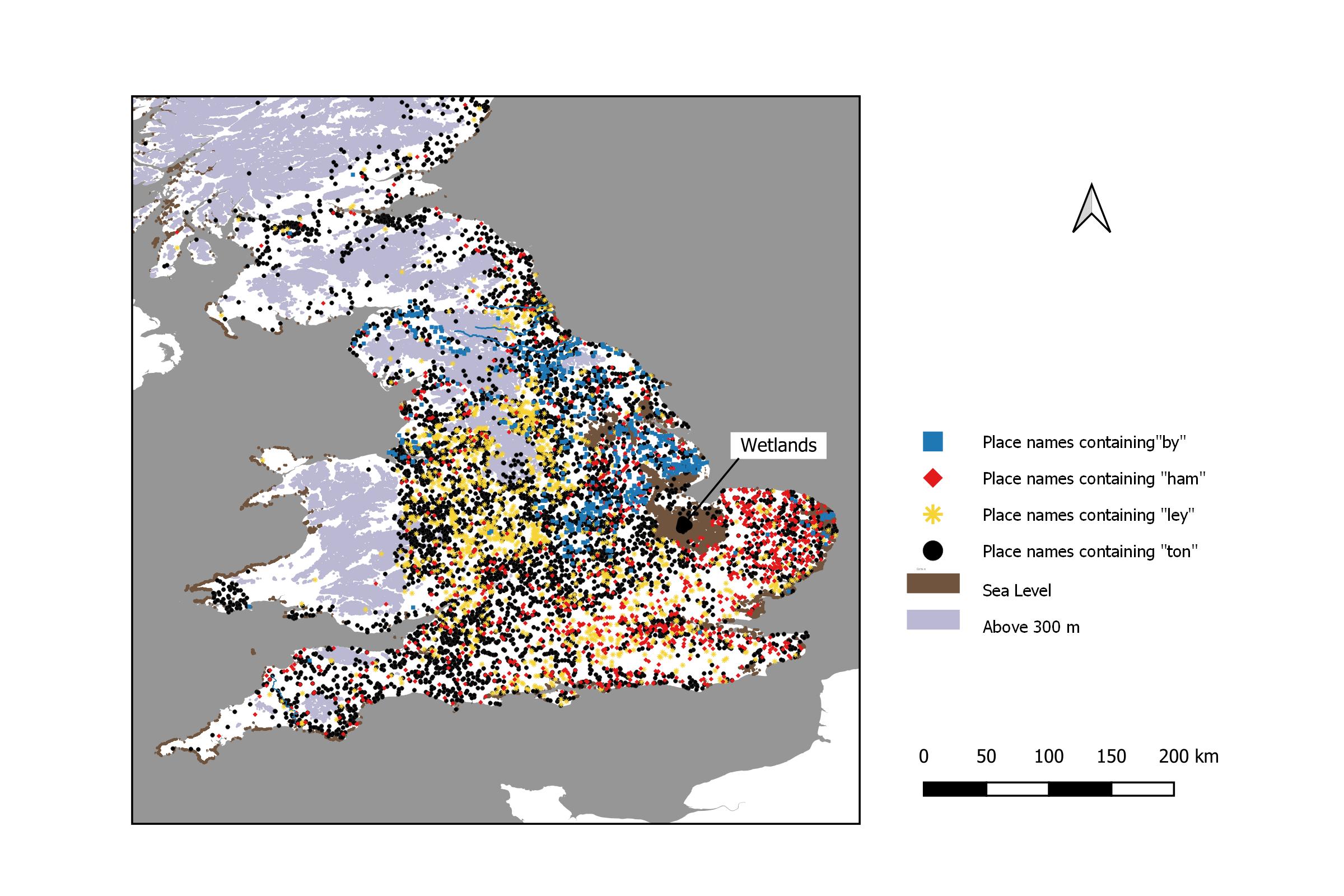

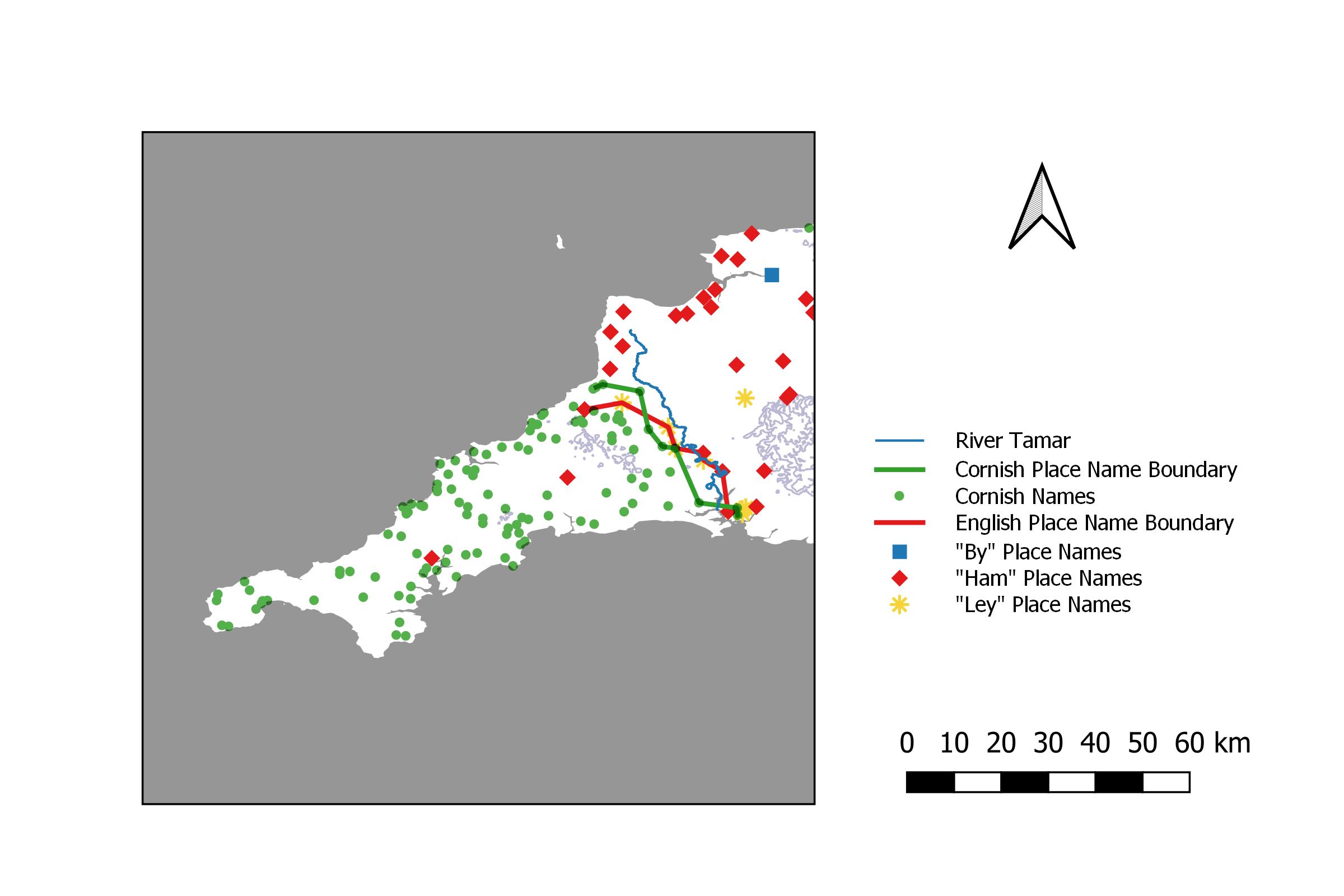

Figure 1 The Distribution of Representative English Place Name Elements.

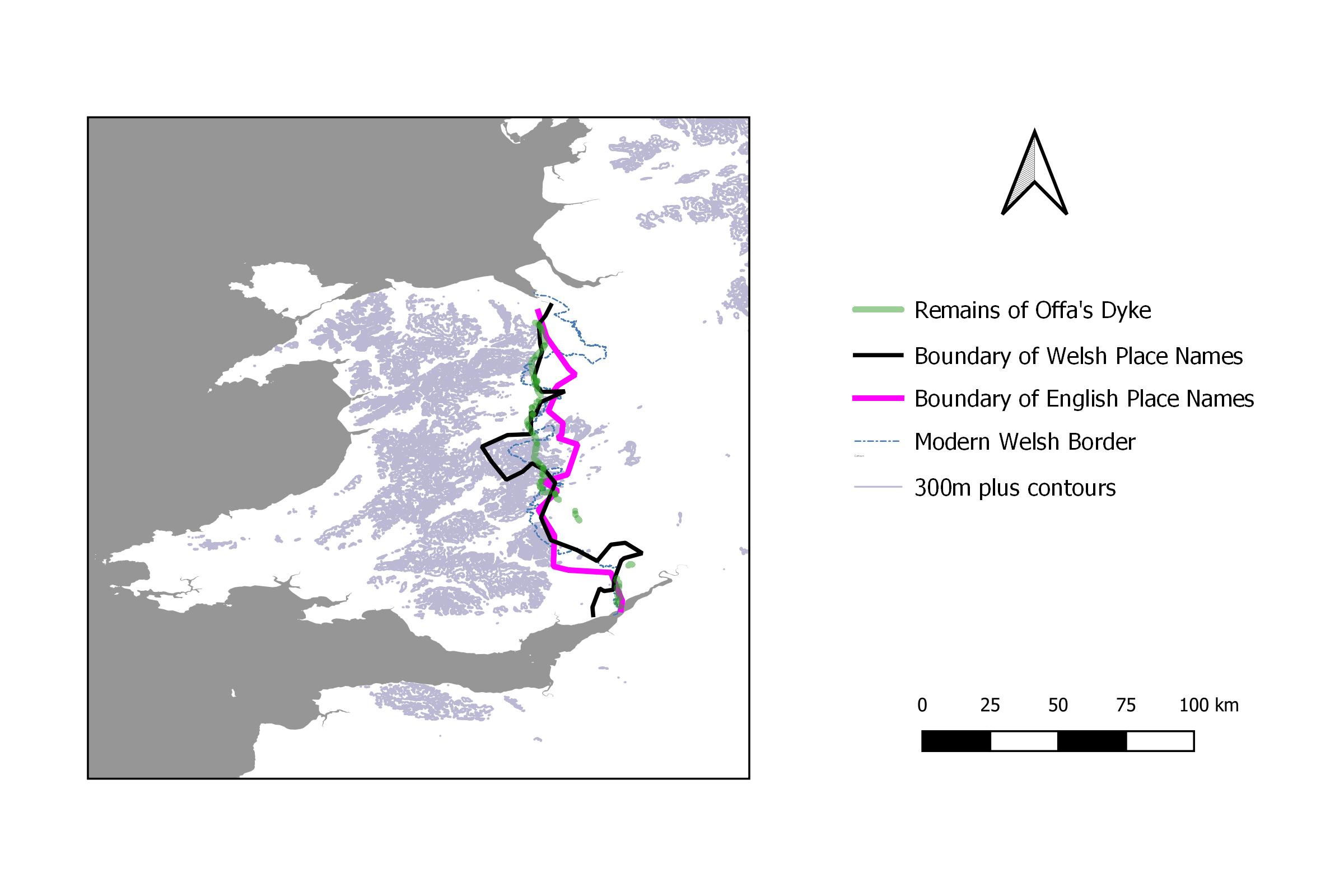

The collapse of the Roman occupation of Britain (c. 410) was accompanied by widespread settlement of Germanic speaking peoples. Some were introduced as Roman auxiliaries, others arrived a little later (Myres, 1969). The incomers formed tribal ‘kingdoms’. The Tribal Hidage (Wikipedia, 2024) is thought to reflect the patchwork of tribes living in what was to become England. Three hundred years later, the Venerable Bede (Miller, Thomas, 1898) referred to these tribes as Angles, Saxons and Jutes. He believed that they originated in Northern Germany and Southern Scandinavia. This note tries to reconstruct place name boundaries at the time of the Germanic settlements.

The invaders named their settlements in their own Germanic languages. I used a “factor analysis” (Buckingham, Bee and Ham Soup - Part 2, Mapping the Geographical Clustering of Place Names, 2022) to find out how place names were distributed. I have taken the single largest place name element in each factor, to represent it. Factor 1 is represented by place names containing the element “ton” (eg Tiverton) which appears 4,581 times in England. Factor 2 is represented by place names containing the element “ley” (eg Barnsley) which appears 1,281 times. Factor 3 is represented by place names containing the place name element “ham” (eg Buckingham) which appears 1,117 times. Factor 4 is represented by place names containing the place name element “by” (eg Barmby) which appears 592 times. This place name element is commonly attributed to Viking Age Scandinavian settlers, although there are good reasons to doubt it as follows: “by” place names are largely absent from other European Viking Age settlements (Buckingham, The Mystery of The "Bees", 2021); modern DNA analysis shows no second wave of settlement after the initial Germanic arrivals (Leslie, Winney, & Hellenthal, 2015); ancient DNA analysis show high levels of Scandinavian DNA among the early (ie pre-Viking) settlements (Gretzinge, 2022).

Maybe I should just say that variants of “ley” and “ham”, were widely used Germanic words and were probably well understood throughout England. Their use by specific groups to describe places may be more about group traditions, than about meanings. For example, the word “field” could be derived from any of the Germanic languages, but it tends to be used more frequently by people who also have a preference for the place name element “ley”.

Figure 1 The Distribution of Representative English Place Name Elements. |

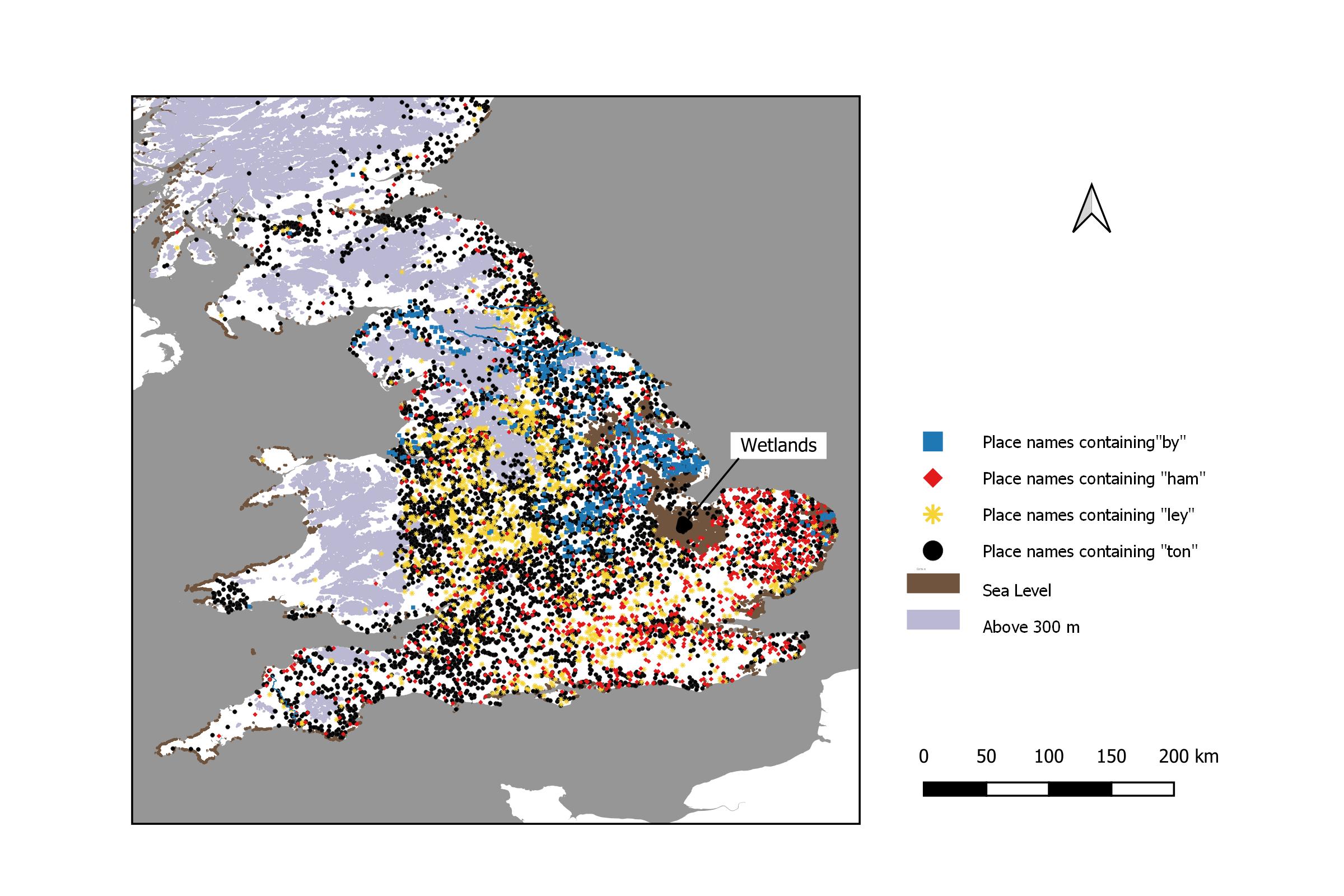

Because “ton” names are so widespread (see Figure 1) and because they continued to be used long after the initial settlements, they are not helpful in understanding those early days. It is possible that they became more widely used when the agricultural workforce came together from their farmsteads into villages, possibly in the sixth century. Certainly by the end of the ninth century, when the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was written, "tun" had become the generic term for a settlement. (For example, in 787 there is mention of the King's "tune" and in 867 Sherbourne was described as a "tun". Interestingly, of the North European Germanic languages, only English commonly uses the term.) Figure 2 replicates Figure 1 but without “ton” place names or contours. This allows us to see more clearly the geographical distribution of the other place name elements.

Figure 2 The Distribution of Representative English Place Name Elements, Excluding "ton" Names and Contours. |

In the absence of “tribal” preferences we would expect to see a more or less uniform mixing of the place names throughout the country. However, this is not the case. We can see some mixing, but we also see a predominance of “ley” place names in the West and North, a predominance of “ham” place names in East Anglia and the South, and a predominance of “by” place names in the arc that includes Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, and Yorkshire and, jumping the Pennines, stretches into Westmorland.

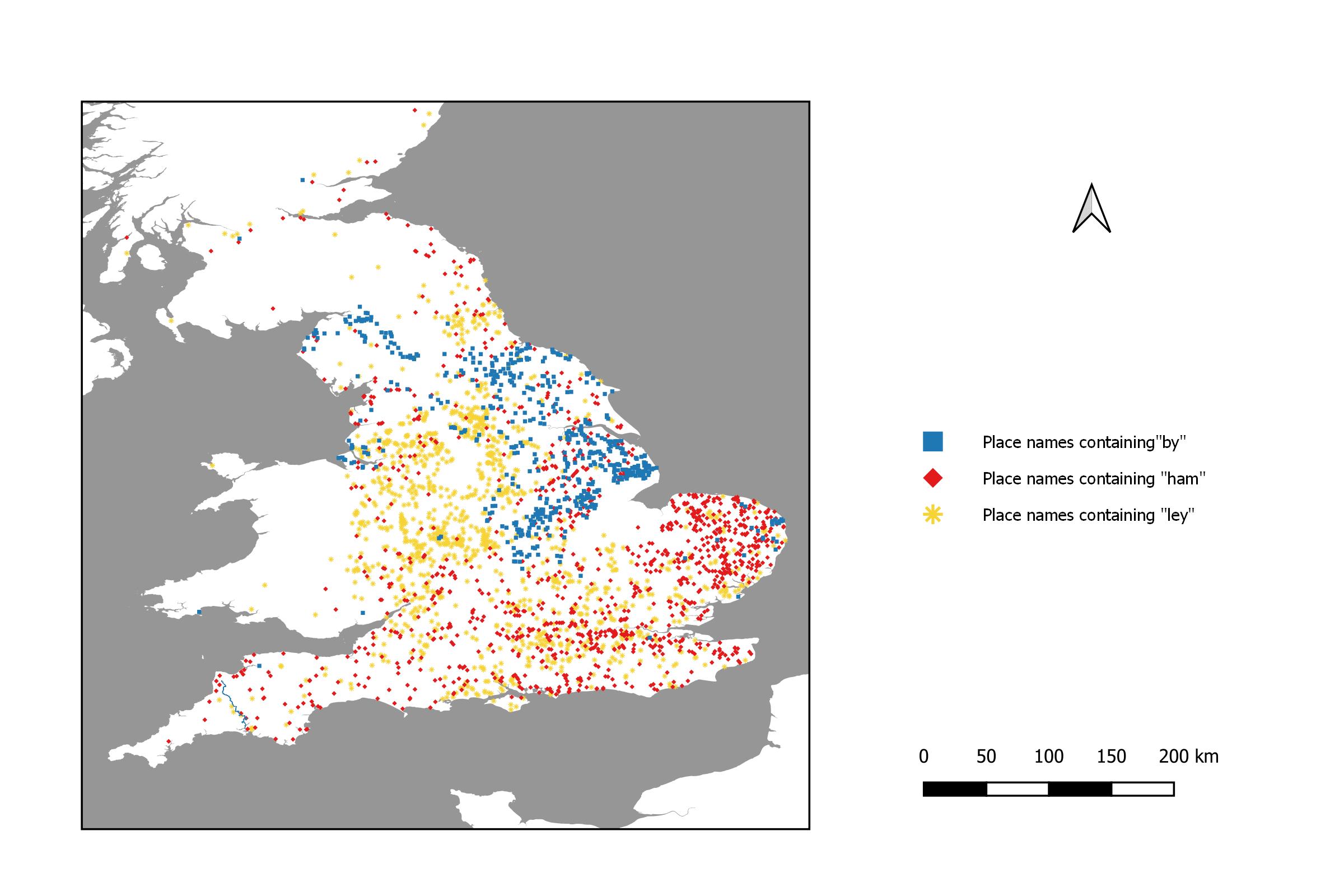

When Germanic tribes established control over England, the native British successfully resisted their expansion in the West and the North. Eventually the borders stabilised for a while, and separate countries appeared in Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. I look at the place name boundaries as they exist today and examine whether or not there is a sharp, distinct boundary between Saxon and British place names. I compare the juxtaposition of the Anglo-Saxon, the Welsh and the Cornish boundaries. I examine where each of the representative English place names are present. Finally, I also consider the possibility of boundaries between the Germanic tribes themselves.

By a border I mean a demarcation between political entities. I use the term boundary as an abbreviation for “place name boundary”. Boundaries can be “sharp” or “fuzzy”, where they overlap. By a “barrier” I mean a geographical feature that hinders the movement of people (such as rivers, mountains or lakes).

I constructed an approximate boundary for English place names along the Welsh border by linking together the most westerly relevant place names containing any of the key elements: “ley”, “ham” and “by”, excluding outlier points which were more than 10 kilometres from their nearest neighbour. Similarly, I constructed an approximate boundary for Welsh place names by mapping all the most easterly relevant place names containing any of the common Welsh prefixes: “Cwm”, “Llan”, “Pen” and “Tre”, also excluding “outliers”. Both English and Welsh boundaries are quite well defined, as well as being close to one another.

Figure 3 A Comparison of English and Welsh Place Name Boundaries and Borders. |

Figure 3 shows the English and Welsh place name boundaries; the remains of Offa’s Dyke; the modern border; and the mountain barriers. In the North, Offa’s Dyke is intact and appears to have prevented place name infiltration (however mediated) in both directions. This breaks down in the South where Offa’s Dyke has been breached in several places. Here, both English and Welsh boundaries appear to have moved westwards in comparison with the remnants of Offa’s Dyke.

In summary, it seems clear that Offa’s Dyke established a border that lasted well into the modern era (especially so in North Wales).

I repeated the method I used to produce boundaries for Wales. Figure 4 shows that the boundaries are quite close together and run along the watershed to the west side of the River Tamar. The high ground behind the river would presumably provide a better defensive barrier. They then turn west at Whitstone, to end at Widemouth Bay. There are a few exceptions but, in general, I would characterise this boundary as regular rather than fuzzy.

Figure 4 Boundaries, Barriers and Border in the South-West. |

As previously, we focus on “by”, “ley” and “ham” place names. There is no clear boundary with the British in the North (see Figure 5); in fact it is difficult to know where to look for one. South of the Tees there is a cluster of “by” place names, so that the river looks suspiciously like a border with the few “ley” and “ham” place names between the Tees and the Weir. However, to the north of the Weir and as far as the River Tyne/Hadrian’s Wall, there is a dense cluster of “ley” place names. To the north of Hadrian’s Wall, English place names again become relatively scarce. The contours do not explain these low densities. The place name boundary between Scotland and England is not even ragged, it is non-existent.

Figure 5 Place Name Boundaries, Barriers and Borders in the North. |

In some districts particular place name types seem to predominate (see Figure 2), implying that linguistic or tribal groups were responsible for particular place name types.

“Ham” names predominate in East Anglia, with a scattering of “ley” names as well as some clusters of “by names along the coast (see Figure 2). The high density of “ham” place names together with the high density of early pottery in East Anglia (Myres J. N., 1969) suggests that this area might have been important in the very earliest Anglo-Saxon settlement.

Heavy concentrations of “ley” names appear in the upper Thames valley, the Midlands, South Lancashire and West Yorkshire. A scattering is also present throughout most of the remainder of England (see Figure 2). The area includes much of the territory of the Mercians, who reached an accommodation with the British tribes in Wales, leading to the construction of Offa’s Dyke. Looking at other associated names from the factor analysis mentioned above, it appears that these people favoured names that referred to their land. Apart from “ley”, (a clearing), we also have “field”, “ac” (an oak tree) and “shaw” (a woodland thicket, cognate with Old Norse "skógr”). The use of “skógr” might imply a Scandinavian origin for these people. By tradition, the Mercians originated in Angeln in the south of Jutland.

“Ley” and “ham” names have only the “fuzziest” of boundaries with each other, merging gently together (see Figure 2). However they both have quite distinct boundaries with “by” place names, for example where the Wash separates “by” and “ham” place names and where the River Tees is a boundary to their northern expansion.

My main conclusion is that place names are quite stable; ie they don’t seem to change much in response to political change. It probably takes large scale population movements to do this. It seems that Wales and Cornwall had some form of stable authority that enabled them to make border agreements. Things seem to have been much more chaotic in Scotland, where Gaels, Picts, Brittonic Celts, and Anglo-Saxons were fighting one another.

The scarcity of “ham” and “ley” place names, in those areas where “by” place names predominate, makes a Scandinavian peasant settlement, at some point in time, almost a certainty. However a Viking Age explanation is difficult to support. All we have is a few ambiguous statements.

For example, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, when Halfdene’s supporters began “ploughing and providing for themselves” in 876 (Swanton, 1996, p. 74) they did so after spending the preceding ten years plundering and living off the land. Presumably they simply settled down to become landowners, and used the existing peasantry on their estates to grow their food.

Another ambiguity relates to the matter of “settlement”. For example, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 880 we read, “Here the army went from Cirencester into East Anglia, and settled that land and divided it up.” (Swanton, 1996, p. 77). With the echoes of nineteenth century colonialism, it might sound as though the land was being taken over by peasant farmers. However, the same word (gesæt) is also used by the authors of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to describe Vikings who had made a temporary base at Fulham, before setting off for the continent (Swanton, 1996, p. 77). From this and other examples in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, gesæt, simply means “staying put”. Accordingly, the written evidence for a peasant takeover of the land by Vikings, with the consequent renaming of their settlements, is no more than flimsy.

Buckingham, J. K. (2022, Autumn). Bee and Ham Soup - Part 2, Mapping the Geographical Clustering of Place Names. Withowinde , pp. 31-32.

Buckingham, J. K. (2021, Summer). The Mystery of The "Bees". Withowinde 198 , pp. 17-24.

Eurogeographics. (2021). Access Data (Open Gazetteer). Retrieved 01 20, 2022, from https://www.mapsforeurope.org/access-data

Giles (translator), J., 1914. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (translated). London: G. Belland and Sons, Ltd.

Gretzinge, J. (2022). Nature. Retrieved 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36131019/

Leslie, S., Winney, G., & Hellenthal, D. (2015). The Fine-Scale Genetic Structure of the British Population. Nature , 309-314. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36131019/[Accessed 2022].

Miller, Thomas. (1898). The Old English Version of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. (e. b. The Old English Version of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Ed.) London: Early English Text Society.

Myres, J. N. L., 1969. Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Myres, J. N. (1986). The English Settlements. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Swanton, M. (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: J. M. Dent.

Wikipedia. (2024, 08 22). Tribal Hidage. Retrieved 09 25, 2024, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tribal_Hidage