We don’t know much about the Great Conspiracy of 367-368, when Roman power in Britain was challenged by Picts, Gaels and Saxons as well as native Britons. However, forty or so years later the Roman armies threw in the towel and abandoned Britain for good. In the vacuum that followed Germanic peoples seized power. The distinguished historian JNL Myres used pottery to examine this process in his book “Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England” (1969). He divided the process into the following phases:

1) Overlap and controlled settlement, c. 360 – c. 410 (in which Germanic settlers were given land by the Roman Army in exchange for military service);

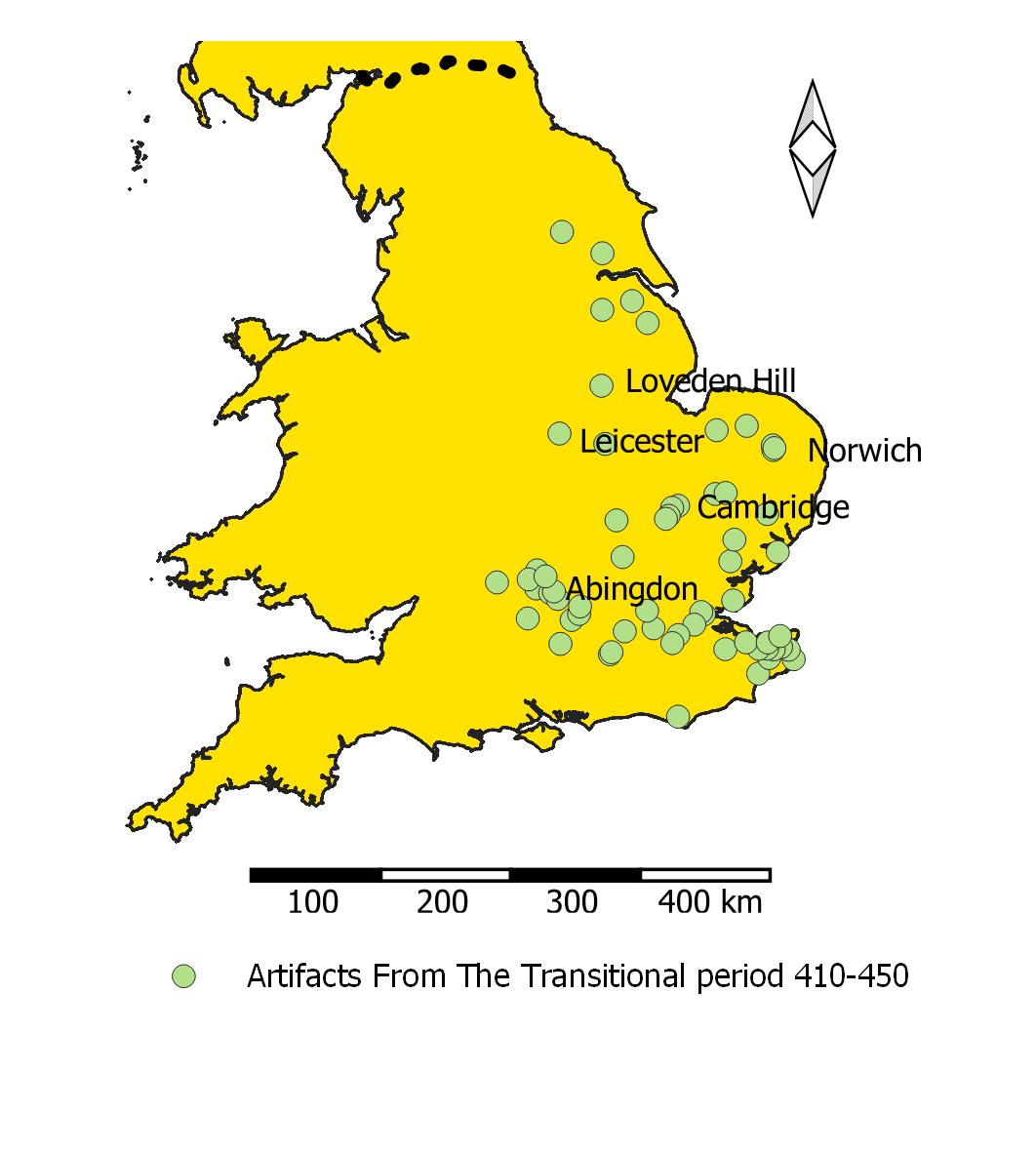

2) Transition, c. 410 – c. 450 (in which the Romanised Britons struggled to maintain some control after Rome’s departure);

3) Uncontrolled Settlement after c. 450 comprising

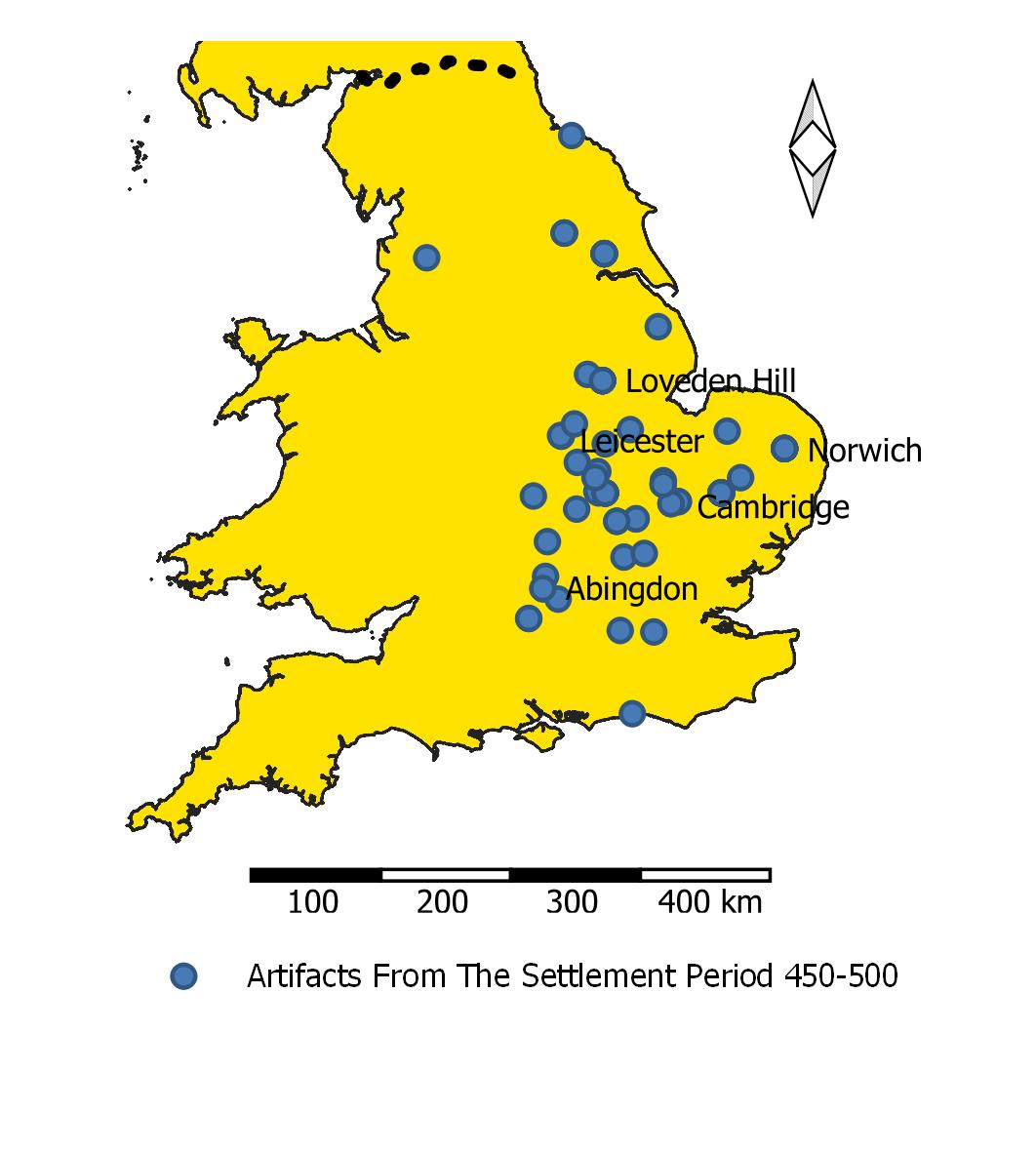

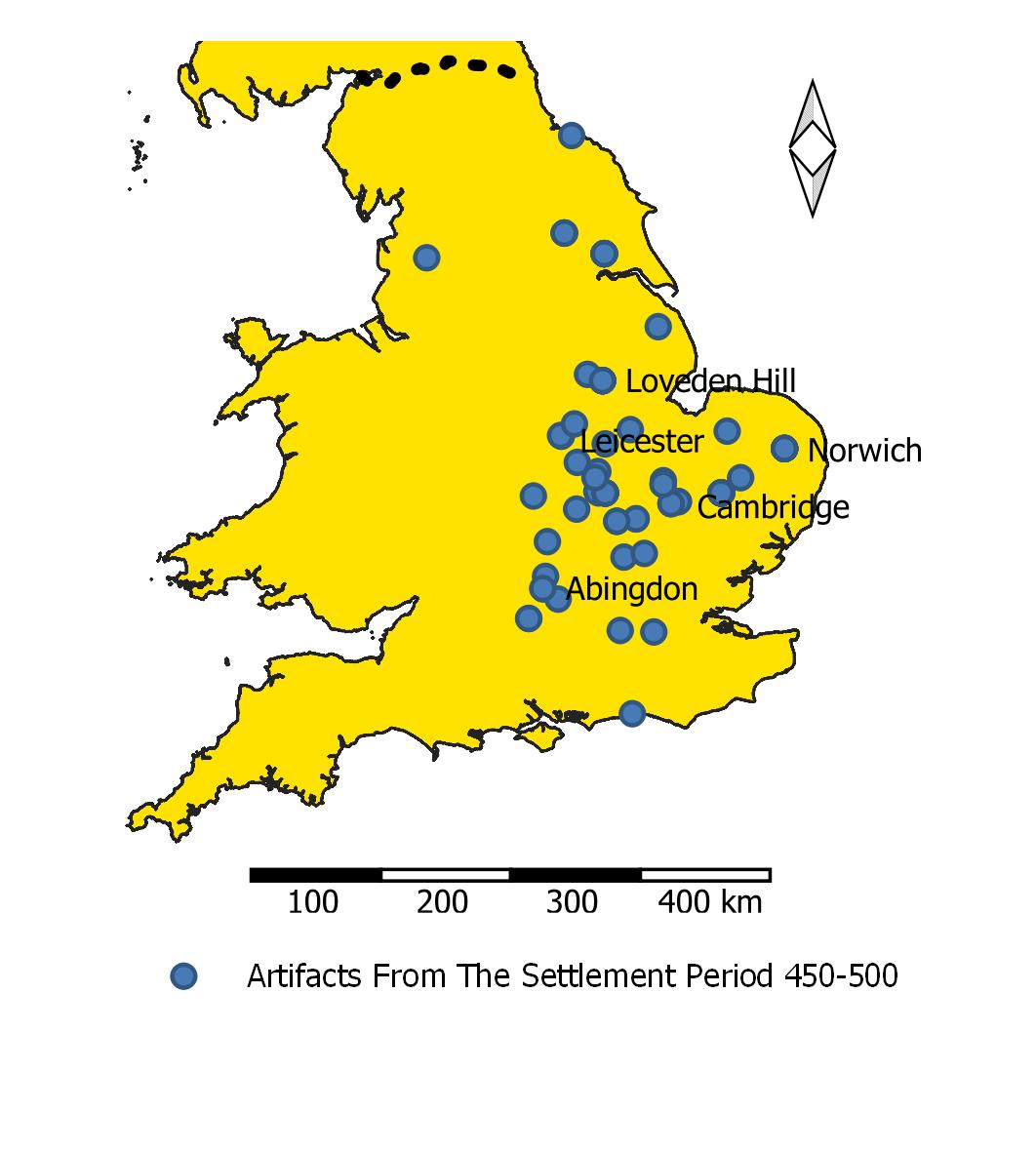

3a) Invasion and destruction, c. 450 – c. 500 (in which Anglo-Saxons and other barbarian people overthrew the remnants of Romano-British civilisation in substantial parts of England);

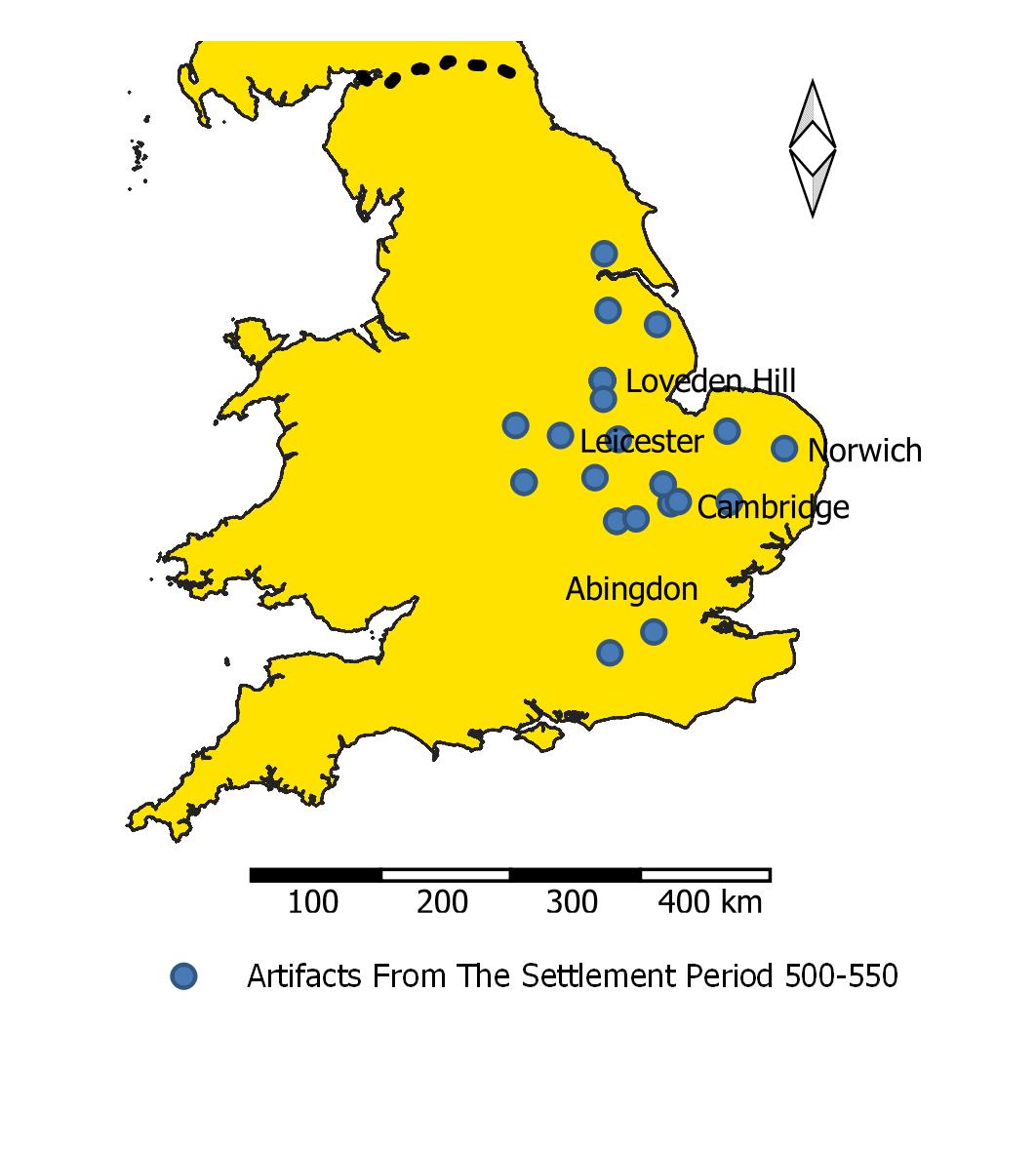

3b) Reaction and British Recovery, c. 500 – c. 550 (in which the Anglo-Saxon advance stalled);

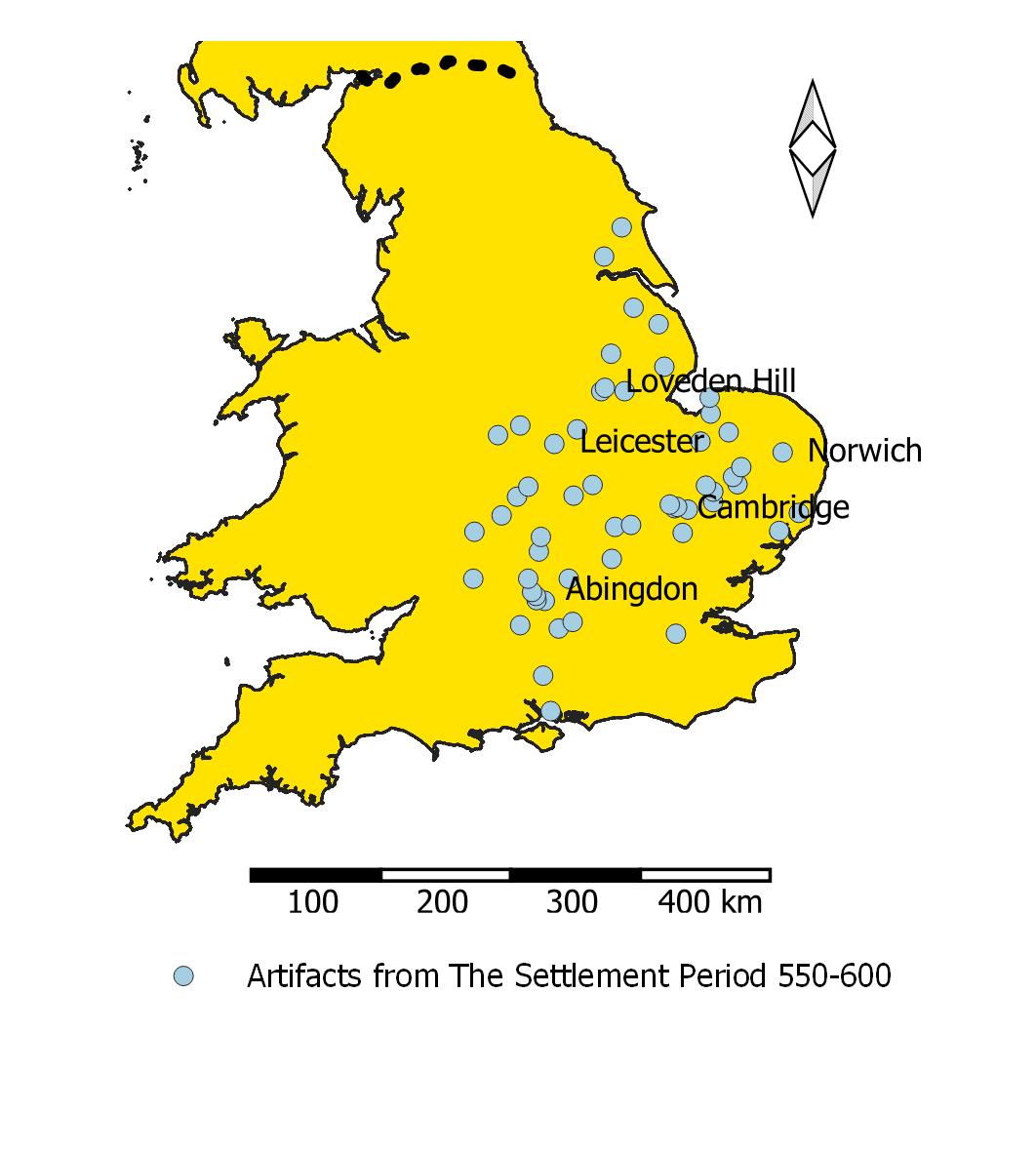

3c) Consolidation, after c. 550 (in which the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms began to take shape and expand).

Myres identified the cultural origin and approximate date of different styles of continental pottery including that of Lower Saxony, Angeln in the South of Jutland, as well as places further north. However, he was keen to emphasise that Saxons and Angles were mixing before they came to Britain, “... some of them (could) as well be termed Anglo-Saxon before the migration to England” p22. Pottery from the cemetery at Perleberg in Northern Germany was used to demonstrate the existence of these mixed groups (“Mischengruppe” in the original German). He quoted the nineteenth century expert JM Kemble who wrote that many of the finds from Perleberg closely resemble Anglo-Saxon pottery found in this country. These mixed people formed the group from whom the Romans recruited “laeti” to police late Roman Britain.

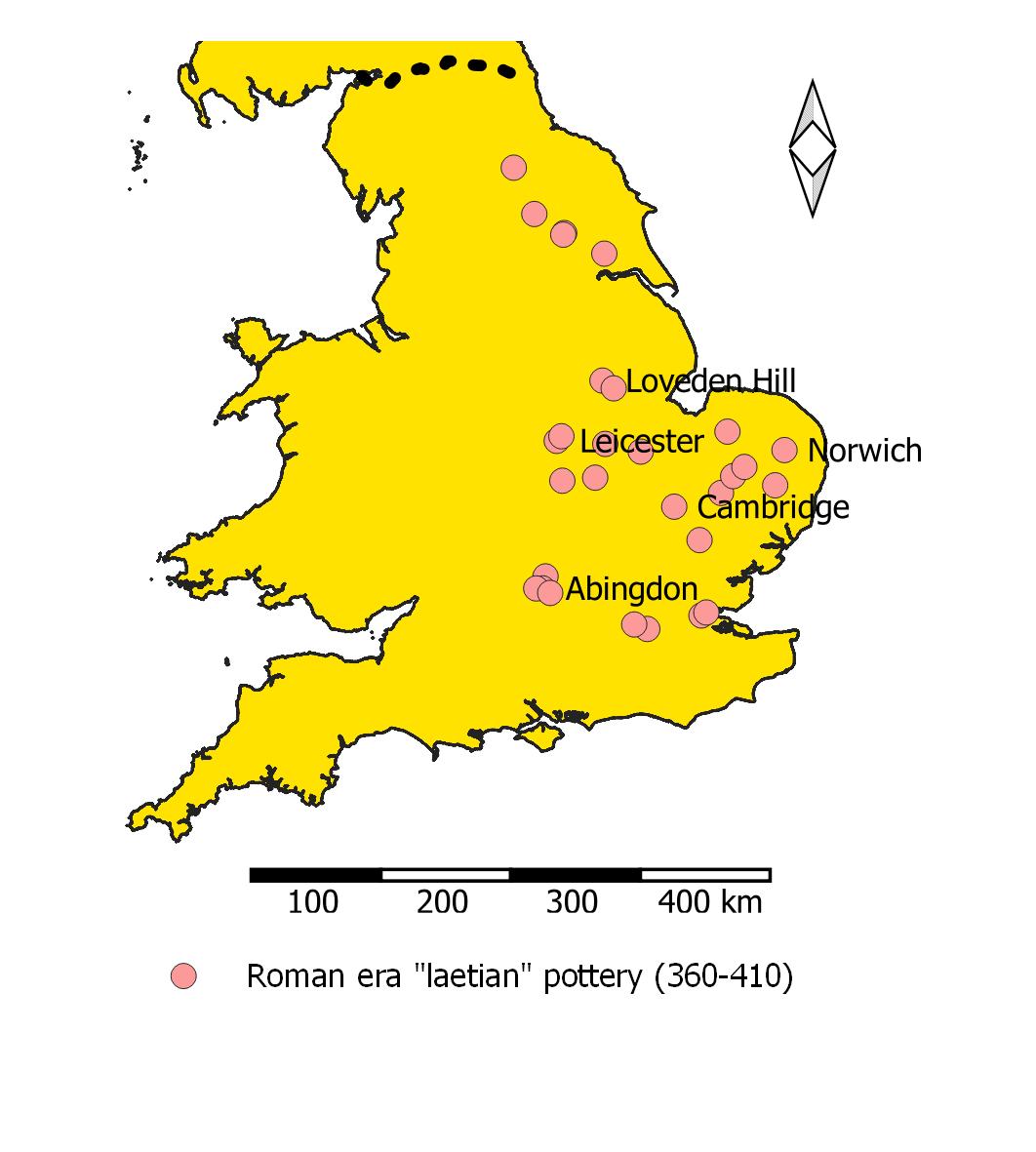

The phase of overlap and controlled settlement, c. 360 – c. 410 Around the time of the Great Conspiracy, an extensive settlement of Germanic laeti was used to strengthen the Roman military power in parts of central and eastern England. This can be seen in the pottery they left behind (see Figure 1). I couldn’t find a generic term for the pottery that they and their descendants produced so, for want of a better word I’ll call it “laetian”. Note that much of Suffolk, Essex and Hertfordshire (the tribal lands of the Trinovante) do not appear to be part of this settlement.

Laeti were garrisoned outside a limited number of native towns notably Caistor St Edmund, (tribal capital of the Iceni), Leicester (tribal capital of the Coritani), and Aldborough, (tribal capital of the Brigantes), as well as along strategic roads. It must have seemed like an army of occupation. They were also garrisoned near London and places on the strategically important lower Thames. Myres uses laetian pottery to demonstrate how these soldiers and their families went on to form the core of Anglo-Saxon settlement of England.

Again Myres looked at the evidence in the form of their pottery. Generally they continued to use the same cemeteries. Their pottery developed into a style called in German “Stehende Bogen” (meaning “standing arches” from the pattern that is etched into the pots).

Cremations were preferred by pagan people and are found mainly to the North of the Thames. To the South of the Thames there seem to have been fewer barbarians and presumably fewer laeti. Their burials are of bodies rather than cremated remains implying that they were influenced by Christian beliefs. Abingdon lies on the boundary between the two zones and contains both cremations and inhumations. Nearby, Reading has Saxon pottery similar to that found at Cuxhaven in Lower Saxony. Kent is somewhat anomalous. It is South of the Thames yet contains evidence of barbarian cremations. The pots are similar to those found in the North of Jutland. Myres (Myres, 1969, p. 95) speculated that they provide evidence of a failed attempt by Britons to use Jutish mercenaries after the Roman departure.

Romanised Britons lingered on in some of the towns, but laetian pottery is not found within the Romano-British towns. The barbarian forces did not mix with the urban sub Romano-British. But there are some new developments, “... pure Angle and Anglo-Fresian pottery (appears) in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, northern (but not eastern) Yorkshire and East Anglia, which could well be the direct consequence of a fresh reinforcement to the northern settlers from the continental Angles at this time.” (Myres, 1969, p. 99). Secondly Jutish pottery is found in Kent. Myres notes that, “ It is significant, in view of the literary traditions of Jutish settlement in Kent that the closest parallels of all come from Jutland itself ...” (Myres p95).

The pottery during this period develops from Stehende Bogen into a form known as “Buckelurnen”, in which the pottery is “buckled” or pushed outwards in a pattern of regular bulges around the perimeter.

In most places Buckelurnen pots are found where Stehende Bogen were found previously; however Myres identifies a few anomalies. In Deira and Lindsey new settlements show stronger links with Southern Scandinavia (Myres, 1969, p. 103). Myres reports that Anglo-Saxon material is not found in the area to the North and East of London (Myres, 1969, p. 104). The Jutish pots have now disappeared from Ken (Myres, 1969, p. 100).

In other areas, the descendants of the laeti seem to be consolidating and expanding into the countryside. Myres (p.114) suggested that they had been joined by others from their homelands, fuelling this expansion. British recovery c. 500 – c. 550

Again the distribution of Anglo-Saxon pottery is, mostly, a continuation of that found before the Roman departure. As Myres says (p. 107), “Broadly speaking, the whole area covered by the great cremation cemeteries of eastern England presents a complete and unbroken range of ceramic fashions from at least the beginning of the fifth to the middle of the seventh centuries”. This period sees the increased use of stamps to produce the decoration on Buckelurnen pottery. However, Myres finds a temporary discontinuity in Anglo-Saxon finds in Sussex, Essex and Hertfordshire. He suggested that this might have been the result of a British recovery following the Battle of Mons Badonicus (see Gildas).

Pottery was evolving from Buckelurnen into the so called “Panel Style”. Figure 1 shows how Anglo Saxon settlement was expanding out of the regions in which Roman laeti were settled.

Myres was reluctant to draw political conclusions, but the selective settlement of laeti in the homelands of specific tribes, particularly stationing them outside their tribal capitals seems strange. I have made some suggestions of my own. It seems to me entirely plausible that it was to control dissidents.

The discovery by Myres of the cultural continuity from Roman times into the late settlement period was both surprising and a remarkable achievement. Figure 5 shows that in most of the regions where Roman era “laetian” pottery is found, developments from that pottery were still being produced nearly two hundred years later. The heaviest concentrations remained in the region encompassed by Abingdon, Loveden Hill (near Grantham, Lincolnshire) and Norwich. This is the area where “ham” place names are most prevalent. They seem to have radiated out from East Anglia (Buckingham, 2022). “ham” names have spread more widely since, but could they also be a marker for descendants of the laetian potters? I also find it interesting that “by” (ie Scandinavian) place names appear to radiate out from Lincolnshire (Buckingham, 2022) and are common in Northern, but (significantly) not Eastern Yorkshire. As I have said previously (Buckingham, 2021) “by” place names are generally not found in Viking age settlements in other countries, so their occurrence in England requires explanation. Moreover, a Viking age explanation cannot account for the lack of these place names in Bernicia which had become Scandinavian territory along with the rest of the “Danelaw”. If a Viking era explanations of the distribution of “by” place names is not tenable, perhaps the Anglian settlement that Myres describes may offer a more plausible explanation. Myres also remarks on the differences in pottery and burial practices to the North and South of the Thames (Myres, 1969, p. 87). There are far fewer Germanic burials in the South (and also in Essex), which Myres suggests may have remained British until well into the sixth century. Genome research was not available to him, but I wonder what he would have made of the finding for the early middle ages that “... CNE (Continental North European or Germanic) ancestry is predominant in central and eastern England, (while) it is much less prevalent in the South and South West of England.” (Gretzinge, 2022).

The article by Gretzinger et al, also supports Myres hypothesis that the immigration of Germanic people was taking place before the Roman departure (Myres, 1969, p. 118). The laeti from the Roman era seem to have stayed. This does not seem surprising. Having been given land for services rendered, the Germanic laeti would have felt that the land they occupied was theirs by right. With families, homesteads and land to support them, these “Romanised” (“Romanised” in the sense that they had been part of the Roman war machine) Anglo-Saxons continued to occupy their lands, when the Romans left. If their role was to keep the “Pax Romana” they may well have felt justified in hostility towards the British native people.

Is it too obvious to mention that there are problems with all three inference techniques that I have mentioned? Pottery provides evidence only where pottery making is in use. This may vary geographically. It also varies culturally. Cremation may have used urns to contain the remains. Inhumation may have used pottery in grave goods, particularly if there was a belief in the use of these goods in an afterlife. DNA may help if bodies were buried and were preserved in the soil. Preservation is more unlikely with cremations, or in some types of soil. Place names can provide information about the language that people used, but groups move through time, and we don’t know when most names were first used. Perhaps it is to be expected that there were cultural differences North and South of the Thames. The Romans had divided the country after years of turbulence and rebellion. Unfortunately, we don’t know the detailed boundaries of these regions (or even how many regions there were), but some sort of boundary along the Thames seems increasingly likely. What Gretzinger saw in the genes, Myres saw in the pottery. But he saw more, he saw a continuity of culture. He saw that parts of central and eastern England carried forward their Roman era Germanic traditions well into the settlement period.

Buckingham, J. K., 2021. The Mystery of The "Bees". Withowinde 198, Summer, pp. 17-24.

Buckingham, J. K., 2022. Bee and Ham Soup - Part 2 Mapping the Geographical Clustering of Place Names. Withowinde, Autumn, pp. 31-32.

Gretzinge, J., et al. 2022. Nature. [Online] Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36131019/ [Accessed 2022].

Myres, J. N. L., 1969. Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.