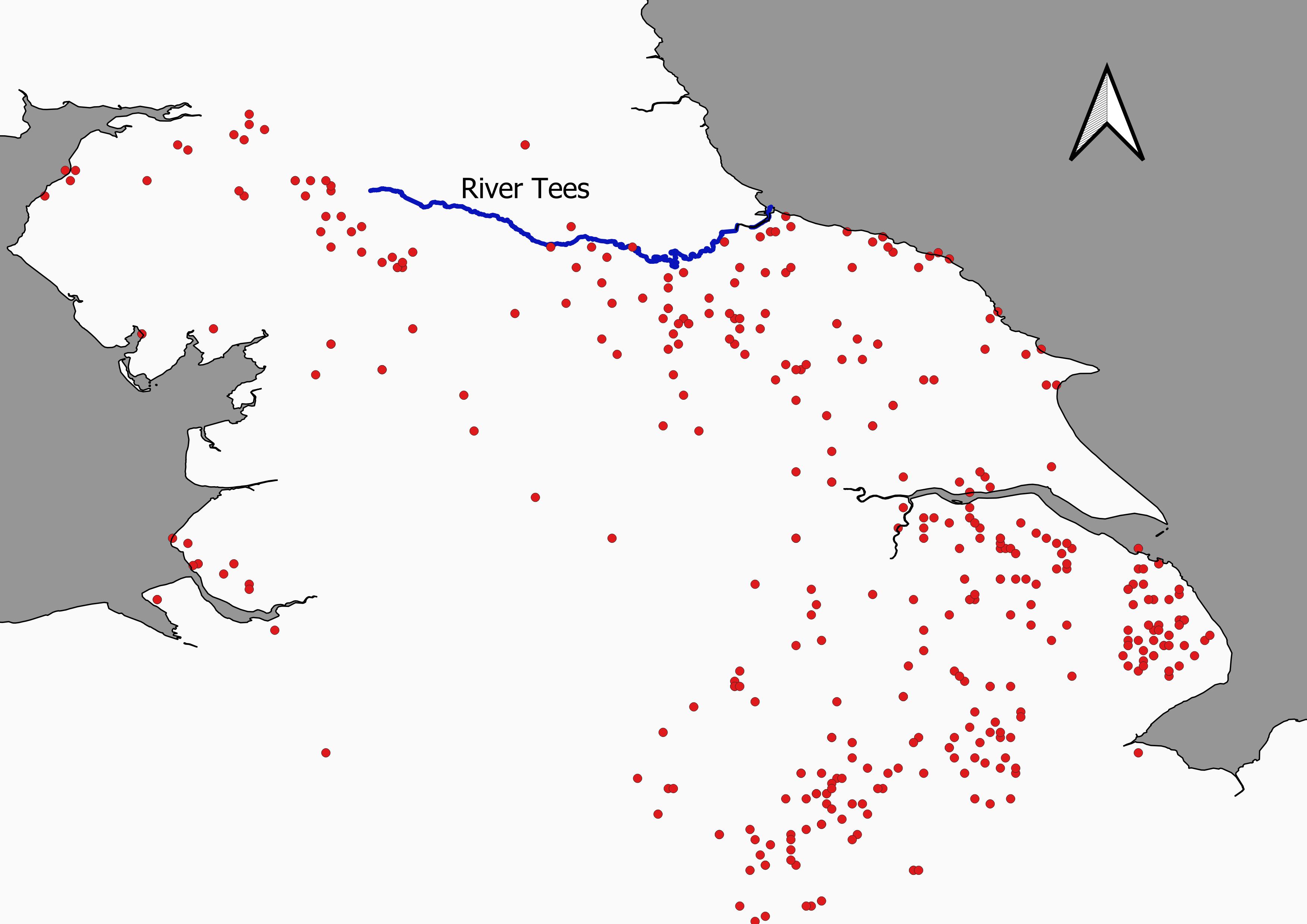

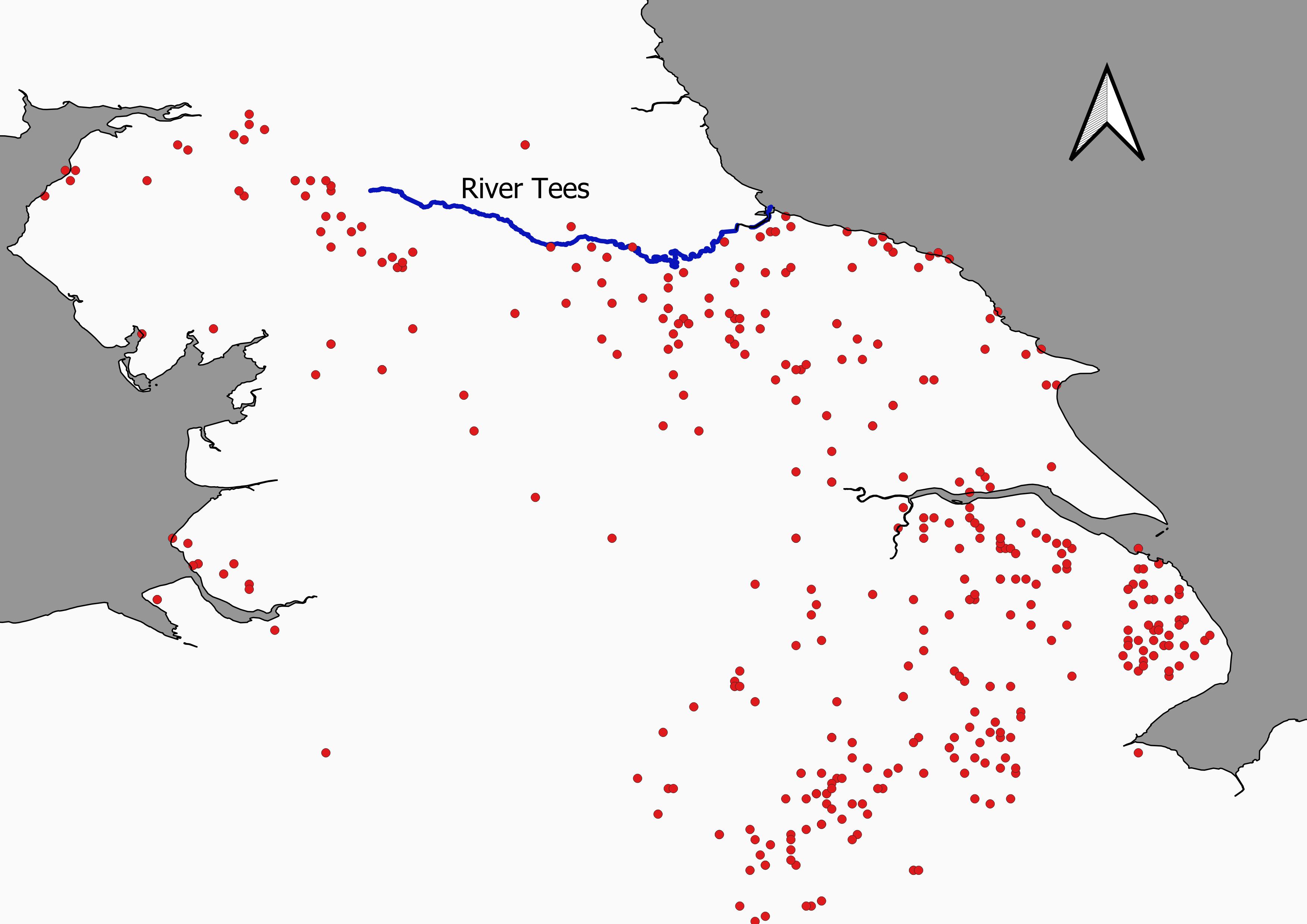

Figure 1. "by" Names in Northern England

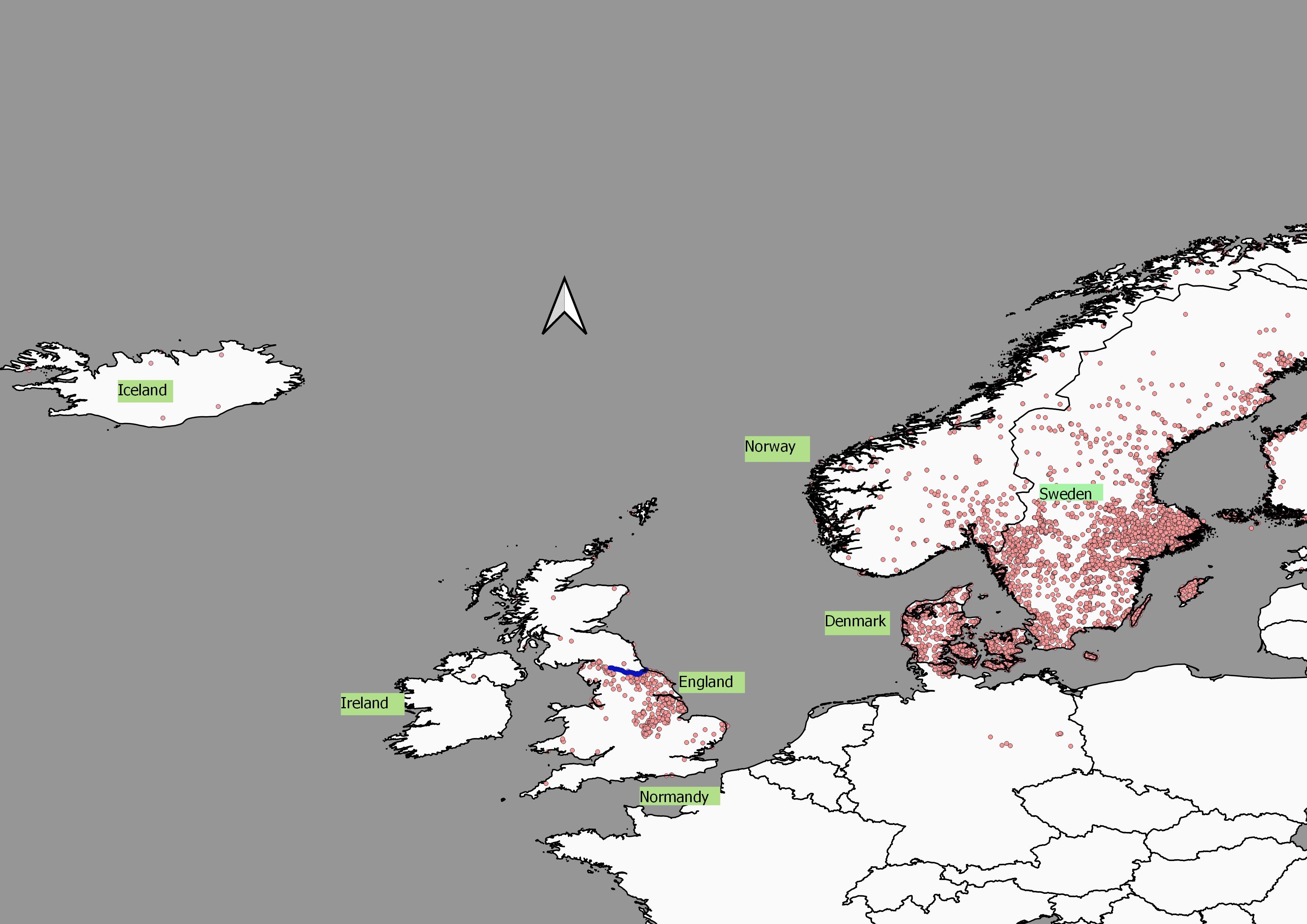

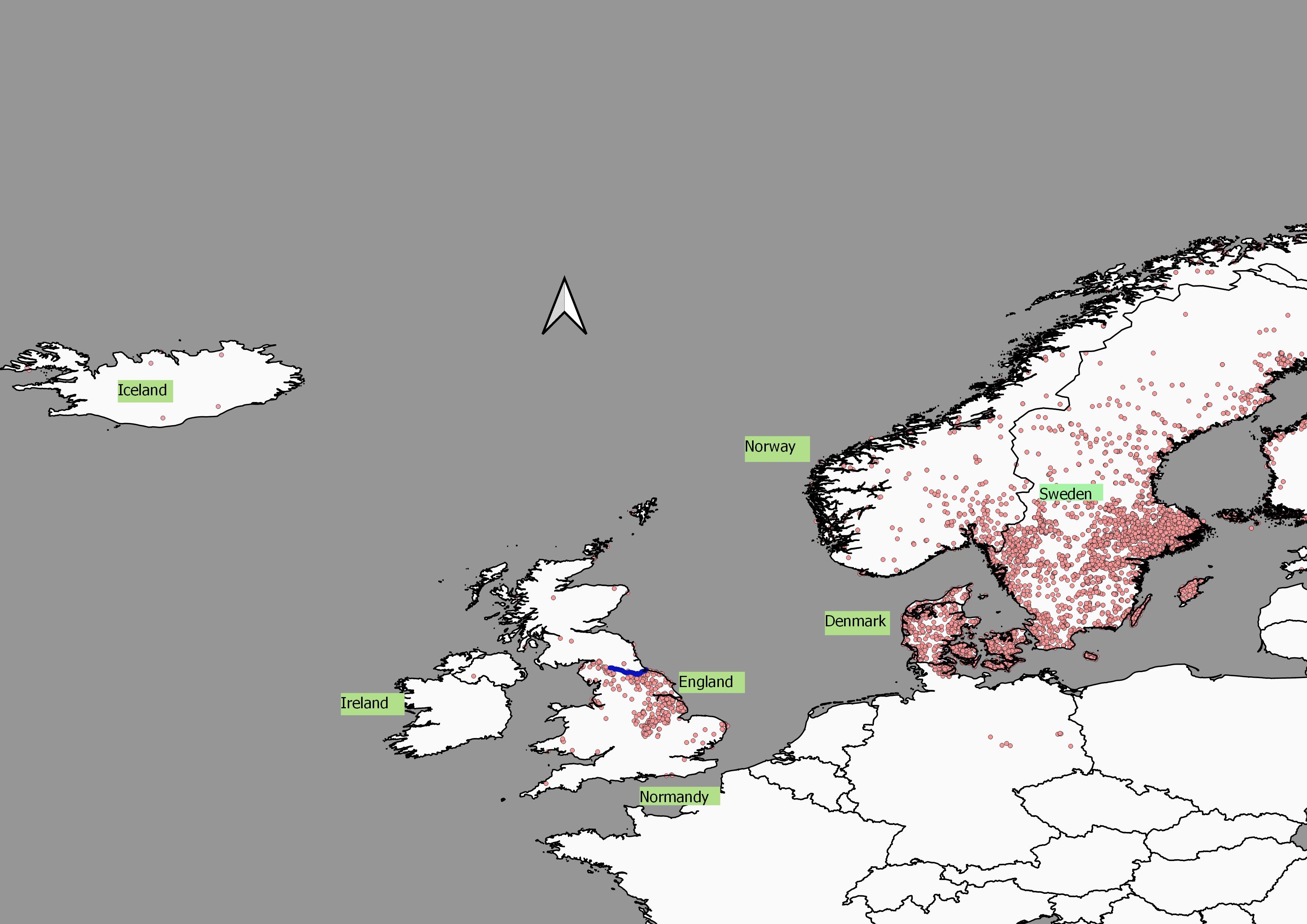

Figure 2. "by" Names in Northern Europe

Permeating the study of Anglo-Saxon history is the belief that it was the Vikings and their descendents who were responsible for the Scandinavian influence on the English language [eg (Gramley, 2019)] including English place names. I am sceptical of this view for a variety of reasons. Here I look at the absence of Scandinavian place names in the areas to the north of the River Tees. It seems to me that this very pronounced linguistic border implies a tribal boundary. I found no record of one during the Viking period. On the contrary what I found was some evidence for power sharing throughout the whole of Northumbria. Without a tribal boundary at the time of the Vikings, I feel that we must look for an earlier one. The only plausible contender is that which existed between the Germanic Kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira. This would imply pre-Viking origins for the Scandinavian language in England. The more orthodox view is that there was some sort of boundary during the Viking period, but that it was not recorded. Effectively this has become the modern consensus, for example the Danelaw, as illustrated in Wikipedia (Anon., 2023), extends only as far as the River Tees and by implication the area to the north was not Viking territory. I examine the evidence for this and find it wanting.

In 865 the "Great Heathen Army" of "Viking" warriors, overwhelmed East Anglia, and went on to subjugate Mercia and Northumbria. Northumbria was quite large. It extended from Edinburgh to Hull, as well as across the Pennines into Lancashire, Cumberland and Westmorland. But Northumbria presents us with a mystery. Although Scandinavian place names are common across a swathe of the Viking regions of Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, they are relatively rare in other Viking regions, for example, west of the Pennines, south of the Wash and particularly to the north of the River Tees where Viking place names stop abruptly (Figure 1). The mystery deepens when we realise that one particular place name element is extremely unusual in other Viking colonies, but, dominates all others in England (Figure 2). This element, "by", usually occurs at the end of place names, and means simply a "settlement". Some authors attribute the missing "by" place names north of the Tees to the existence of an independent country there - a country that resisted Viking settlement - yet is invisible in the contemporary records. I prefer to believe that they should look further back in time to the post Roman period, for the origin of these "by" place names. Following the departure of the Roman forces, England was taken over by the Germanic mercenaries who were abandoned there by the Romans (Myres, 1969). Soon after, fresh Germanic settlers arrived, including people from Scandinavia (Myres, 1969) (Gretzinge, 2022). These groups coalesced into various Kingdoms. It is these different Kingdoms that might well have had their own languages, ethnic origins and used their own place name elements. Unfortunately, they left no written evidence of their speech. By the 7th century, two of these Kingdoms, Bernicia (the land to the north of the Tees, stretching far into modern day Scotland) and Deira, roughly corresponding to Yorkshire joined together to become known as Norðhymbrum (Northumbria). This union came about through dynastic marriages, and probably would have had little effect on the lives of ordinary people. My guess is that the linguistic differences can still be heard in the dialect voices of Northumberland/ Durham and Yorkshire.

Figure 1. "by" Names in Northern England |

Figure 2. "by" Names in Northern Europe |

The primary written source for the events of the Viking period in England is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (ASC) (Swanton, 1996). It takes the form of a set of brief annual reports of important events, battles, the death of rulers and prelates etc. It was originally produced in Winchester, the capital of Wessex. Although the earliest version has been lost, a copy survives and is known as "Manuscript Version A" or the "Winchester Manuscript". It covers Scandinavian activity in England until 924 in some depth, however, the coverage after that is somewhat erratic. Fortunately copies of Manuscript A, were distributed to scholars elsewhere. They sometimes pick up where Version A leaves off. They also include some additions from a local perspective. Manuscript C occasionally reports events relating to Mercia that are not reported elsewhere. Manuscript D was believed to have originated in Northern England and is useful for adding details to the period of the Anglo-Saxon resurgence in Northumbria under King Edward and his successor, King Athelstan. To ensure academic rigour in my account of events, I searched through all mentions of Northumbria in all versions of the ASC and reproduce them below for readers to examine themselves.

Anglo-Saxon society was deeply divided into "noblemen and commoners" (Blair, 1995), p 259. The lords fought and feasted. They had the horses and the weapons with which the warring Kingdoms clashed. The peasants were an essential part of the machinery that turned fallow land into feasts. They owned little, but produced all. The Scandinavian society from which the Vikings came was much the same, although perhaps a degree or so more egalitarian.

In 867, Northumbria was involved in civil war. While rival kings fought for the throne, the Great Heathen Army arrived from Scandinavia. After a brief, but successful campaign in East Anglia, they quickly captured York, the Northumbrian capital. The Northumbrians put aside their differences to join forces against a common enemy, but were heavily defeated. Both contesting Kings and much of the Northumbrian aristocracy were killed. The remainder made peace.

We don't have any written records of the terms of the truce (unlike the case of King Alfred and Guthrum in East Anglia), but it seems that an accommodation was reached between the surviving Northumbrian aristocracy and the Vikings. This makes a great deal of sense when we consider the alternatives:

Battle weary, after 8 years fighting and pillaging for food, the Viking warlord Halfdene returned North and settled himself down " ... Halfdan divided up the land of Northumbria; and they were ploughing and were providing for themselves ..." - ASC). The Great Heathen Army had divided. Halfdene kept Northumbria and shared it with his men. His compatriots in Mercia and East Anglia did likewise. However, settling down was a double edged sword. They now had the wealth that came from the land they occupied. On the other hand, they could no longer hit and run, disappearing into the woods and wildernesses. Now, having towns and villages to defend it gave Wessex and Mercia fixed targets to hit. They could play the Scandinavians at their own game. They could take the battle to them.

Halfdene had previously established relationships with the Northumbrian aristocracy (867). When he returned, he shared out the land, not only with his comrades, but also with the native Northumbrians. We know this from the ASC where, for example in 924, Edward's peace treaty refers to, "all those who live in Northumbria, both English and Danish and Norwegians and others". There is no mention of separate Kingdoms in Northumbria (moreover, at no time is there any reference to battles between different parts of Northumbria). This reveals the existence of a historic compromise in which coexistence and power sharing were the norm. Halfdene did not have the manpower to do other than compromise. It has been estimated (Sawyer, 1997) that the numbers of ships reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle would imply an army of about 1000 soldiers. The arable land they had to share can be estimated (Broadberry & Campbell, 2011) for the year 1290 as follows (acres): Eastern Counties, 2,810,950; NE Midlands, 1,200,070; North East, 1,622,420; North-West, 708,220 or 6,341,660 in total. Even if we double Sawyer's estimate, it would amount to about 3,170 acres to be managed by every warrior. Some form of delegation was inevitable. Since his men were largely illiterate. He would also need some clerical assistance, to keep track of land grants and other agreements. This was a job that the church had traditionally performed. They drafted charters and provided safe storage for them. By way of comparison, William of Normandy had a force of approximately 5,000 warriors (Gravett, 2005) as well as churchmen at his disposal (Douglas, 1957).

Nothing else was mentioned of Northumbria in the ASC for nearly twenty years (894). If there were to be any large scale peasant settlement of Scandinavians into Northumbria, this would have been the time. However there is no mention of the dispossession of native peasant farmers, nor any mention of Anglo-Saxons being sold into slavery. In 894, the uneasy truce between Saxon and Dane was over. Viking Northumbria seems to have joined forces with Viking East Anglia and two Scandinavian armies who had been busy in Europe. These were no "hit and run" raiders. The foreign armies were large. One required 250 ships, and the other 80 ships to transport them. Assuming they each carried a force of 40 men, that implied an army of 13,200 warriors. This was not an army that could melt into the countryside. This was an army for full scale battles. But Wessex and Mercia were better prepared than they had been. Battles raged, but the Scandinavians were contained within Andred Forest (the Weald of Kent). Eventually they broke out but were overwhelmingly defeated in 897. The foreign armies broke up, with the warriors making their own way to Northumbria, East Anglia, or even back to Europe. Note that when the ASC spoke about Northumbria it was as a single land, there was no suggestion that it was divided into the lands north and south of the Tees.

It is interesting that there seems to have been friendly relations between all the Northumbrian nobility, Viking and Saxon. For example, in 901, when Alfred's nephew, Ethelwold, needed an army to prosecute his hereditary claim to the throne of Wessex, he saw no problem going to the melting pot of Northumbria for assistance from Vikings and Anglo-Saxons. In 906, all Northumbrians worked together. Again Northumbrians joined forces with East Anglia, and again they were jointly defeated. In 911 an army from Northumbria raided Mercia. King Edward of Wessex defeated the raiders. Northumbria lost two Kings in the process, King Eowils and King Halfdene, both were Scandinavian in origin. For the moment the Scandinavians had passed their peak. If they were to colonise Northumbria in mass they would surely have done it by now.

In 915, Wessex and Mercia were establishing strongholds in the southern parts of Northumbria. In 918 Ethelflaed (Edward's sister and Alfred's daughter) was about to be recognised as some sort of overlord by the people of York, but died before this could be ratified. In 923 Edward was also probing the south of Northumbria where he was reported repairing and garrisoning the Roman fort of Manchester. In 924 the nobles of Northumbria acknowledged Edward as their king. In 924, the regime changed. Edward, king of both Wessex and Mercia became the overlord of Northumbria. His vassals were "Raegnald and Eadwulf's sons".

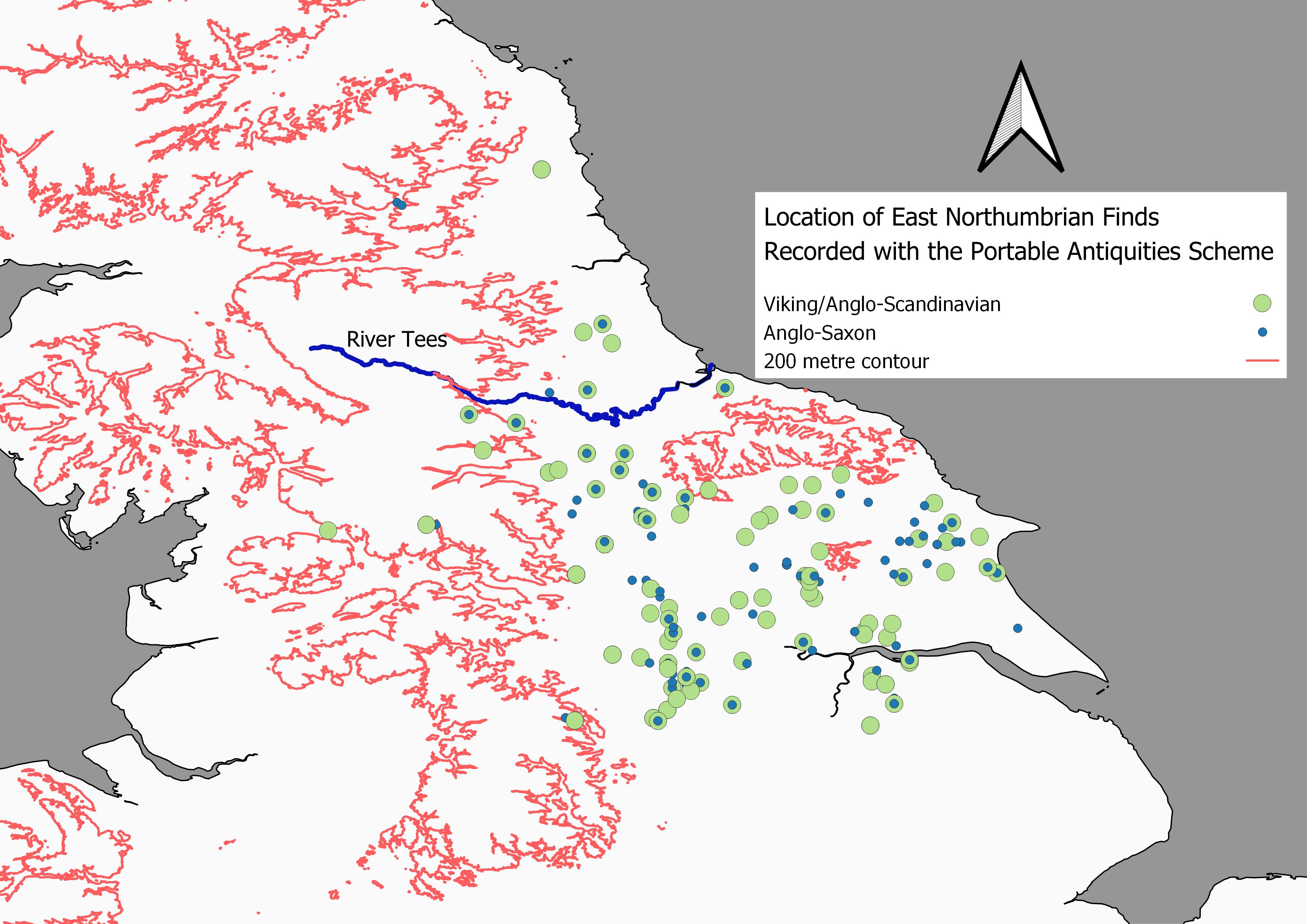

To corroborate the written sources I looked at the archaeological evidence from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS, 2024). The scheme records the finds of amateur archaeologists. With the preponderance of utilitarian items, belt buckles, spindle whorls, pins etc, the scheme is particularly useful in identifying peasant settlements. I used the PAS "Advanced Search" procedure, from their "finds.org.uk" website. I selected individually for the two European Regions of the "North-East"and "Yorkshire and Humber"; selecting also for items from the "Middle" of the "Early Medieval" period. Data were exported in Google Earth (KML) format. The North-East search produced 41 results, Yorkshire and Humber produced 760 results. The data were imported into the QGIS mapping package and mapped using the "Description" field as either "Anglo-Saxon", "Anglo-Scandinavian"/"Viking". If Viking archaeology were absent to the north of the Tyne, this would suggest that an independent Kingdom did indeed exist there and the absence of Viking place names would be explained. If there were Viking finds to the North if the Tyne, then that would suggest that the opposite were true, ie that there was Viking activity in the area. However, we could not rule out the possibility that the area was inhabited by Saxons with a penchant for Viking paraphernalia. The archaeological evidence is not clear cut. There are some Scandinavian artefacts to the North of the Tees, but not many. Taken in isolation, this might be interpreted as a few exceptional finds such as items lost in transit, trophies etc. On the other hand, it might simply imply that the amateur archaeologists (who form the contributors to the PAS scheme) were not particularly active in the area, perhaps because of unfavourable geology, topography (see the prevalence of high ground to the north of the Tees in Figure 3), or the relative isolation of the area. One way of checking this is to look at the relative prevalence of other finds. If the area is generally a poor source of archaeology, this could account for the low number of Viking age finds. This does indeed prove to be the case. Figure 3 maps out finds from the middle of the Early Anglo-Saxon period showing Viking related finds and Anglo-Saxon finds. It shows that, generally speaking, there are relatively few finds to the North of the Tees, but that this is equally true of Viking related and Anglo-Saxon finds. I would tentatively suggest that Viking people were present both North and South of the Tees. If so, this would imply that we need to look for a pre-Viking explanation for that absence.

Figure 3. Portable Antiquities Scheme - Finds in Northumbria |

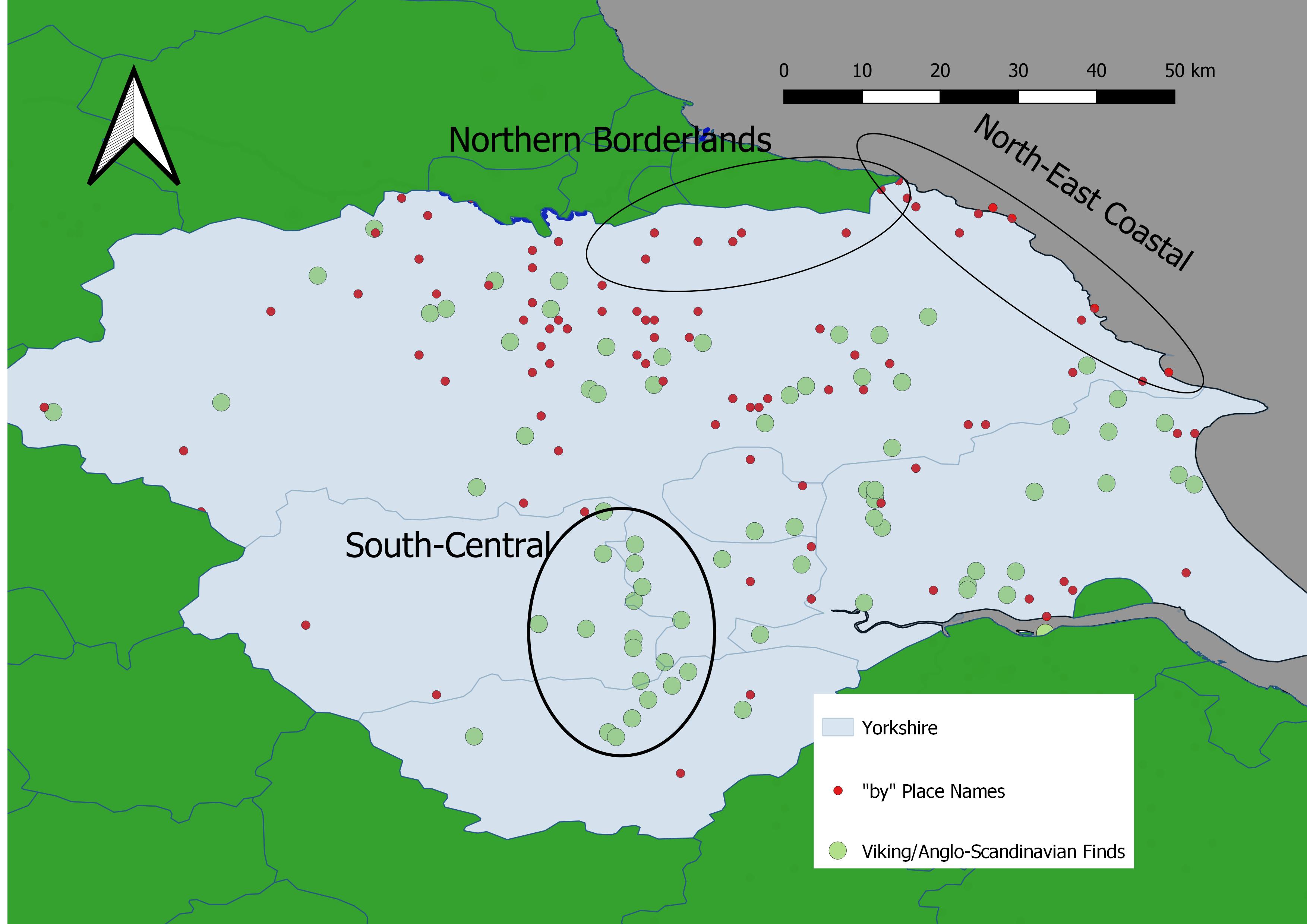

We can use the information from the Portable Antiquities Scheme at a more detailed level. Figure 4 focuses in on Northumbria south of the Tees (defined in terms of the modern county boundaries of Yorkshire). Looking again at the middle of the early Anglo-Saxon period, but restricting our attention to Viking related finds we compare their distribution with the distribution of place names ending in "by" (as a marker for Viking population settlement) see Essay 1. If "by" names originated in the Viking age, we would expect Viking place names and Viking archaeology to occur together. Where Scandinavian place names exist but there is no Viking age archaeology, we might be suspicious that the place names did not arrive with the Vikings. However we could not rule out the possibility that metal detectorists have not been active in the area. Such an absence can be seen in the Northern Borderlands and the North East Coastal area of Figure 4. Stronger evidence against a Viking origin for the "by" place names would be the existence of Viking Archaeology in places where there are no such names. This is the case in the South-Central area shown in Figure 4. It is harder to think of an explanation in this case.

Figure 4. Portable Antiquities Scheme - Scandinavian Place Names and Viking Archaeology |

In conclusion, recalling that my concern is to discover whether there was an autonomous kingdom north of the Tyne that prevented the establishment of Scandinavian settlements there, for the entire period of Viking hegenomy from 867 until 923, there is no mention of such a kingdom. I could find no evidence to support the commonly held view that the Viking lands ended at the River Tees. Furthermore, right up to the point when Edward was threatening the independence of Northumbria, there was no suggestion that a free Saxon Northumbria joined forces against their Viking neighbours or "overlords". As the well known phrase goes, "absence of evidence is not evidence of absence (of a proposition)", however, where we expect to see evidence of a proposition and there is none, we should be sceptical.

I have attempted to assemble a complete list of extracts relating to Northumbria, from all versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, up until the subjugation of the Vikings by Wessex. There is very little other contemporary written evidence, apart from a few inconclusive fragments from Irish sources. I hope that by reproducing these extracts from both sources people will be able to check my inferences and form their own conclusions. Note that there is an old translation freely available on the internet (Giles (translator), 1914). The original text of the Winchester version of the Chronicle (Anon., n.d.) is also available.

| Corrected Year | Extract | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 867 Version A |

"This year the army went from East-Anglia over the mouth of the Humber to York in North-humbria. And there was much dissension among that people, and they had cast out their king Osbert, and had taken to themselves a king, AElla, not of royal blood; but late in the year they resolved that they would fight against the army; and therefore they gathered a large force, and sought the army at the town of York, and stormed the town, and some of them got within, and there was an excessive slaughter made of the North-humbrians, some within, some without, and the kings were both slain: and the remainder made peace with the army." |

Northumbria was in turmoil when the Vikings arrived. Note that the remnants of the Northumbrians were not replaced by the Vikings, but rather, came to terms with them. Some form of cohabitation is implied. |

| 875 Version A |

"Here the raiding army went from Repton, and Halfdan (Halfdene) went with some of the raiding army into Northumbria, and took winter-quarters on the River Tyne; and the raiding-army conquered that land ...." |

The conquest of Northumbria does not distinguish between different parts. On the contrary, the Tyne ie to the north of the Tees, is explicitly included in Northumbria. |

| 876 Version A |

"And that year Halfdan divided up the land of Northumbria; and they were ploughing and were providing for themselves " |

This is sometimes taken to imply a widespread peasant settlement. An alternative interpretation is that, after many years plundering for wealth and food they became landowners in their own right. |

| 894 Version A |

"... Then those who dwelt in Northumbria and East Anglia gathered some hundred ships and went around South ... " |

After 18 years of domination the Vikings launch an all out attack on Wessex with the help of other Viking armies from the continent. This attack fails and the hegemony passes to Wessex. Note that there is no mention of any partition in Northumbria, it is all referred to as if it were one. Neither is there any mention of division between the Danes and the Anglo-Saxons in East-Anglia. |

| 895 Version A |

Then when they (members of the Viking invading armies) turned back from Wales with the war booty they had taken from there, they went across the land of Northumbria and East-Anglia so that the army could not get at them until they came east of the land of Essex, on an island which is out in the sea that is called Mersea. " |

This illustrates that parts of Northumbria were so far South that they lay between Wales and Essex. |

| 897 Version A |

.".. Then the summer after in this year , the raiding army went off, some to East Anglia, some to Northumbria, and those that were without money got themselves ships there ..." " ... The same year the raiding armies in East Anglia and Northumbria greatly harassed Wessex ..." |

Apparently some of the raiding army had had enough, the poorest taking ships to go abroad, although others were still harassing Wessex. Again Northumbria is spoken of as a single realm. |

| 901 Version A |

"... he stole away by night and sought out the raiding army in Northumbria ..." |

This refers to Ethelwold, who as the son of Alfred's older brother, was directly in line to the throne of Wessex, and who went to the Northumbrians for help to obtain his kingdom. Again, Northumbria is referred to as if it were a single kingdom. |

| 906 Version A and Version D |

" and in the same year they confirmed the peace at Tiddingford just as King Edward determined, both with East-Angles and with the Northumbrians." |

Again, Northumbria is referred to as if it were a single kingdom. |

| 907 Version C |

"Here Chester was restored." |

Included only because Chester was in Northumria. |

| 911 Version A |

"... the raiding army (originally the Anglo-Saxon word "here") in Northumbria broke the peace (on Norðhymbrum according to original manuscript A 910), and scorned every privilege which King Edward and his councillors offered them, and raided across the land of Mercia ..." "... (King Edward) put the raiding army (from Northumbria) to flight, and killed many of it. And there was killed King Eowils and King Halfdan , and Jarl Ohter, and Jarl Scurfer, ..." |

The raiding army is "in Northumbria", perhaps suggesting that it is among the other Northumbrians. The kings who were killed were both Scandinavian. There is no mention of a separate non-Scandinavian Kingdom in Northumbria. The kings who were killed were both Scandinavian. There is no mention of a separate non-Scandinavian Kingdom in Northumbria. |

| 915 Version C |

"Then in this the next year after midwinter, [was built] that stronghold at Chirbury, and then at Weardbyrig; and in that same year before midwinter at Runcorn (in Northumbria). " |

Queen Ethelflaed of Mercia was winning back land from the Vikings. |

| 918 Version C |

"And also the York folk had promised her (Ethelflaed), and some of them so granted her by pledge, some confirmed with oaths, that they would be at her disposition. But very quickly after they had done that, she departed (died) ..." |

Ethelflaed's campaign against the Vikings resulted in a victory acknowledged by the people at York, but she died before getting there. |

| 923 Version A |

"... he (King Edward) ordered another army, also from the nation of the Mercians, to go to Manchester in Northumbria, and to improve and to man it. " |

This provides evidence that Manchester was in Northumbria. |

| 924 Version A |

"... And then the King of Scots and all the nation of Scots chose him (Edward) as their father and lord, and [so also did] Raegnald and Eadwulf's sons and all those who live in Northumbria, both English and Danish and Norwegians and others; and also the King of the Strathclyde Britons and all the Strathclyde Britons." |

Note that in Version A, the Scandinavian Raegnald is subservient to West Saxon Edward, whereas in Version D the Scandinavian King Raegnald wins York. Eadwulf and hence presumably his sons were Anglo-Saxon. With Edward now overlord of Northumbria, it would not be surprising if he were to delegate power to the Anglo-Saxons living alongside the Scandinavians in Northumbria. |

| Version D | "Here King Raegnald won York. " | |

| 925 Version D |

"Here King Athelstan and Sihtric, king of Northumbria, assembled at Tamworth on 30th January, and Athelstan gave him his sister. " |

Sitric was one of the Vikings from Ireland. He was related to Raegnald. Surely Athelstan was acknowledging Sihtric as King of Northumbria by agreeing to this marriage. |

| 926 Version D |

"... And Sihtric perished and King Athelstan succeeded to the kingdom of Northumbria, and he governed all the kings who were in this island; first Hywel , king of the West Welsh, and Constantine, king of Scots, and Owain, king of Gwent, and Ealdred, Ealdwulf's offspring, from Bamburgh ... " |

We don't know the circumstances under which Sihtric perished, however, Athelstan took over Northumbria, perhaps through his sister, Sihtric's wife. This succession remains a matter of debate (Downham, 2007). Whereas Hywel, Constantine and Owain are referred to as Kings, Ealdred is simply referred to as Eadwulf's offspring from Bamburgh. |

There are a few fragments relating to Northumbria in the Irish records. They were mentioned by McGuigan in his PhD thesis (McGuigan, 2015). Unfortunately I did not find them helpful. The Annals of Clonmacnoise (Mageoghagan, 2016) entry for 904 reports that "... Edulfe King of the north Saxons died." Presumably he was the Edwulf who was father of the sons of Eadwulf mentioned in the ASC entry for 926. In 928 the annals report that, "...Adulf m'Etulfe king of North Saxons died." Presumably he was one Eadwulf's sons mentioned in the ASC for 924. The Annals of Ulster entry dated U913.1 (Hennessey, 1887), reports that, " ... Etulb, King of the North Saxons ...". The translator assumed this to be a reference to the death of Ethelwold (who sought help from the Northumbrians to fight for his hereditary right to Wessex following King Alfred's death). Not only was the mention enigmatic, but the dates differ by some eight years from that recorded in the ASC entry for 905 (Swanton, 1996). Note that none these mentions of North Saxons necessarily implies a separate kingdom to the North of the Tees. With reference to Edulfe King of the North Saxons, we should not be surprised that power sharing could result in kings of both Saxon and Viking heritage in Northumbria, particularly in the wake of the resurgence of Wessex and Mercia under Edward and Ethelflaed.

Anon., n.d. Manuscript A: The Parker Chronicle. [Online] Available at: https://asc.jebbo.co.uk/a/a-L.html [Accessed 12 02 2024].

Blair, P. H., 1995. An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

Broadberry, S. & Campbell, B. M., 2011. Arable Acreage In England , 1270-1871. s.l., s.n.

Douglas, D., 1957. The Norman Episcopate before the Norman Conquest. The Cambridge Historical Journal, 13(2), pp. 101-105.

Downham, C., 2007. Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press Ltd.

Giles (translator), J., 1914. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (translated). London: G. Belland and Sons, Ltd.

Gramley, S., 2019. The history of English an Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge.

Gravett, C., 2005. Hastings 1066:The Fall of Saxon England. s.l., Praeger Publishers.

Gretzinge, J., 2022. Nature. [Online] Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36131019/ [Accessed 2022].

Hennessey, W. M., 1887. The Annals of Ulster. [Online] Available at: https://archive.org/stream/annalauladhannal01royauoft/annalauladhannal01royauoft_djvu.txt [Accessed 12 February 2024].

Mageoghagan, C., 2016. The Annals of Clonmacnoise; being annals of Ireland, from the earliest period to A. D. 1408. Translated into English A. D. 1627. [Online] Available at: https://archive.org/stream/annalsofclonmacn00mage/annalsofclonmacn00mage_djvu.txt [Accessed 11 February 2024].

McGuigan, N., 2015. PhD Thesis Neither Scotland nor England: Middle Britain, c.850 to 1150. [Online] Available at: https://www.academia.edu/13635613/PhD_Thesis_Neither_Scotland_nor_England_Middle_Britain_c850-1150" [Accessed 11 February 2024].

Myres, J. N. L., 1969. Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

PAS, 2024. database#. [Online] Available at: https://finds.org.uk/ [Accessed 7 February 2024].

Rye, E., 2016. Dialect in the Viking-Age Scandinavian diaspora: the evidence of medieval minor names - York Research Database. [Online] Available at: https://pure.york.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/dialect-in-the-viking-age-scandinavian-diaspora-the-evidence-of-m [Accessed 30 01 2024].

Sawyer, P. H., 1997. The Oxford Illustrated History of Viking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stenton, F. M., 1947. Anglo-Saxon England. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stephenson, C., 1943. Feudalism and its Antecedants in England. The American Historical Review, 48(2), pp. 245-265.

Swanton, M., 1996. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: J. M. Dent.

Wikipedia, 2023. Danelaw. [Online] Available at: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danelaw [Accessed 31 01 2024].