When the tribal migrations of farming people arrived in England after the Roman departure, those who took the land by force would have chosen their own place names in their own languages. Germanic place names are still visible today. My hope is to use them to examine the origins of the people who renamed the Celtic places of England.

In considering this, I ask two related questions:

1. Do some place name elements commonly group together?

2. How are groups distributed around the country?

Part 1

I began with a list of 107 place name elements (eg "ham", "holme", "ton" etc) from Wikipedia (1). In case different spellings reflected different linguistic origins, alternative spellings of the same word were included separately. A list of 23,465 place names was obtained from an EU data base (2). Each of these place names was examined and flagged up if they contained the place name elements. Place name elements were excluded if fewer than fifty places contained them, leaving 48 in all. It was beyond my resources to examine all place names individually, but where it was obvious that one element was part of another, only the latter was counted. For example, "ing" is part of "king", accordingly such words were counted as having only the element "king". In contrast and by way of example, places containing the text "ingham" were counted as having both elements "ing" and "ham".

I divided England into 413 squares, each square being twenty miles east to west and twenty miles north to south when measured on a Mercurator projection. This converts to approximately 12 miles by 12 miles crow fly distances or approximately 144 square miles. For each square I counted the number of places having each of the place name elements.

I used factor analysis to determine whether the various place name elements were likely to appear together in the same squares. This technique creates artificial variables to represent hypothetical groups (the "factors"), and reports how closely correlated the actual variables are to those hypothetical groups. The technique allows the researcher to explore various hypotheses rather than examining the statistical significance of one that has previously been stated. Accordingly they are free to choose from a menu of alternative techniques. I examined the "relative importance" (eigenvalues) of each factor to decide how many factors to include. I found that the reduction in eigenvalues levelled off after the fifth factor, accordingly I restricted the analysis to the top five. Factor analysis reports on the correlation between all variables and all factors. Most of those variables are poorly correlated with the factors. I have listed the five most closely correlated place name elements in each factor, provided they had factor loadings greater than 0.3. These comprise the place name groups used in the rest of this article.

For each place name group, I list the place name elements it contains and examine the linguistic origins of each. Not to pre-judge the results, I searched both North and West Germanic sources. Arjen Versloot (3) was helpful for a historical perspective on Frisian place names. The Department of Nordic Research at the University of Denmark was useful in tracking down the origins of common place name endings in Denmark (4). Of the most well known Victorian sources, Sweet (5) was helpful for Anglo-Saxon vocabulary but not for etymology. For etymology Bosworth-Toller (6) is preferable. Glosbe (7) provides (among other things) some translations for Old Fresian and Old Norse. ArchMaps (8) provided a list of archaic place name elements and their meanings. Wordsense (9) provided the origin and history of place name elements. Etymonline (10) and Wiktionary (11) were also helpful. Where I failed to track down Old Fresian or Old Norse, I looked for modern equivalents in West Fresian, Dutch and Danish.

Factor analysis shows that some groups of place name elements do indeed commonly appear in close proximity to one another. Potentially this raises the possibility of common origins. Definitions of the various place name elements (shown in italics) are taken from reference (1).

Group 1's most important elements are: "ton" (n=4,581), "ing" (n=1,759), "ford" (n=709), "nor" (n=420) and "bury" (n=269). There is no clearly identifiable common origin for the principle elements of Group 1. With the exception of "ford", all of these place name elements have cognate forms in both North Germanic and West Germanic languages, which might help explain their ubiquity

| Name Element | Modern meaning | Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| "ton" | "Enclosure", "estate" or "homestead". | "The Wiktionary(11) entry for the etymology of the Old Norse tun gives the following derivation, "Proto-Germanic tūną, also from Proto-Celtic dūnom. Jensen (12) says that tún went out of Scandinavian use before the Viking Age. It translates from West Frisian as "garden" ie a fenced-off place for growing vegetables. Dun is equivalent in Gaelic and means "a fortification". "Dun" occasionally morphs into "tun" and modern "ton" (eg Eþandun becomes modern English Edington). Accordingly "ton" can be derived from a variety of Germanic and Celtic roots. |

| "ing" | "People of". | The University of Denmark (4) website reports that variants are found in both Friesland and Denmark. |

| "ford" | "Ford", "crossing" or "road". | Glosbe.com (7) gives the Old Frisian equivalent as "Forda". I failed to find an early Norse translation. The modern Danish equivalent is "vadested" (7). Accordingly it seems that the origin is likely to be from the Old Fresian (ie West Germanic rather than North Germanic). |

| "nor" | "North". | This element collects "north" and its abbreviations. Sedgefield (13) gives the Anglo-Saxon as "norð”" Glosbe gives modern West Fresian as "noard" and Old Norse as "norðr" |

| "bury" | "fortified enclosure". | Has the same meaning as burgh (a fortified enclosure)(8). The German word "burg" (a castle) is cognate as is Old Norse "borg" from the proto Germanic burgz (11). |

Group 2's most important elements are: "ley" (n=1,281), "field" (n=557), "ac" (n=264), "brad" (n=82) and "shaw" (n=67). Most of the place name elements in Group 2 have direct equivalents in both West Germanic and North Germanic. The exception is "shaw", which only appears in Scandinavian sources. If the derivations are correct then on the balance of probabilities, we would have to place the origins of Group 2 names in Scandinavia. Given the possible significance and the relative infrequency of "shaw" names, I examined their distribution visually. Reassuringly "shaw" names do seem to crop up in all of the areas where other Group 2 place names are present. Remarkably four of these place name elements refer to woodlands or clearings.

| Name Element | Modern meaning | Derivation | "ley" | ("a woodland clearing"). | Wiktionary (11) gives similar alternative forms in Dutch ("lo"), Old Saxon ("lōh") and Old Norse ("lōh"). |

|---|---|---|

| "field" | ("open land, a forest clearing"). | Wordsense (9) gives alternative forms as - West Frisian "fjild", Dutch "veld", German Feld", Swedish "fält". |

| "ac" | ("acorn, or oak tree"). | Sweet (14) gives "ac" as "oak". The West Frisian is "iik" and modern Danish is "eg" (7). | "brad" | ("broad"). | I couldn't find anything similar in Old Frisian or Old Norse. The closest equivalent in modern Danish is "bred" and in modern Dutch is "breed". |

| "shaw" | ("a wood, a thicket"). | Derived from Old English "sceaga", cognate with Old Norse "skógr". I couldn't find any cognate word in West Frisian. It is listed as an English word in a Dutch Thesaurus (15). The West Fresian equivalent of "thicket" is "dikke". |

Group 3's most important elements are: "ing" (n=1,759), "ham" (n=1,117), "den" (n=350), "street" (n=159) and "stead" (n=98). Only "street" seems to have unequivocally Frisian origins. On balance, therefore, we should attribute Group 3 place names to West Germanic origins.

| Name Element | Modern meaning | Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| "ing" | Discussed above under Group 1. | |

| "ham" | ("farm, homestead, settlement"). | A quick look at a map of Friesland will show the place name ending to be common there as "um". Their origins are discussed by Arjen Versloot (3). The same is true in Denmark where many place names also end in "um". Some of these derive from "hjem" (meaning "home") and some are an inflection with the meaning "in" or "by". An extensive discussion is available at the University of Denmark's website (4). Although spelled "ham", as a place name ending, the usual pronunciation of "ham" in England is "um" (in contrast to the American pronunciation as in "Birmingham, Alabama"). In summary, cognates of "ham" are to be found widely throughout the Germanic lands. |

| "den" | ("valley"). | The Frisian equivalent is dene (10). The Old Norse for a valley is "dalr(7)", which becomes "dale". |

| "street" | ("road"). | Bosworth (6) gives the Anglo-Saxon strǽt with etymology including: O. Sax. O. L. Ger. stráta : O. Frs. stréte : O. H. Ger. stráza O. These all have origins in Latin. In Old Norse where Latin was less influential, the equivalent is "gata" (7) and hence "gate" in Scandinavian influenced parts of England. |

| "stead" | ("place, enclosed pasture"). | In Danish "sted" has the generic meaning of "place". It also has West Germanic origins. Bosworth-Toller gives the Anglo-Saxon as stede with etymology "O. Sax. stedi: O. Frs. sted, stid, steith: O. H. Ger. stat; f. locus: Icel. staðr." |

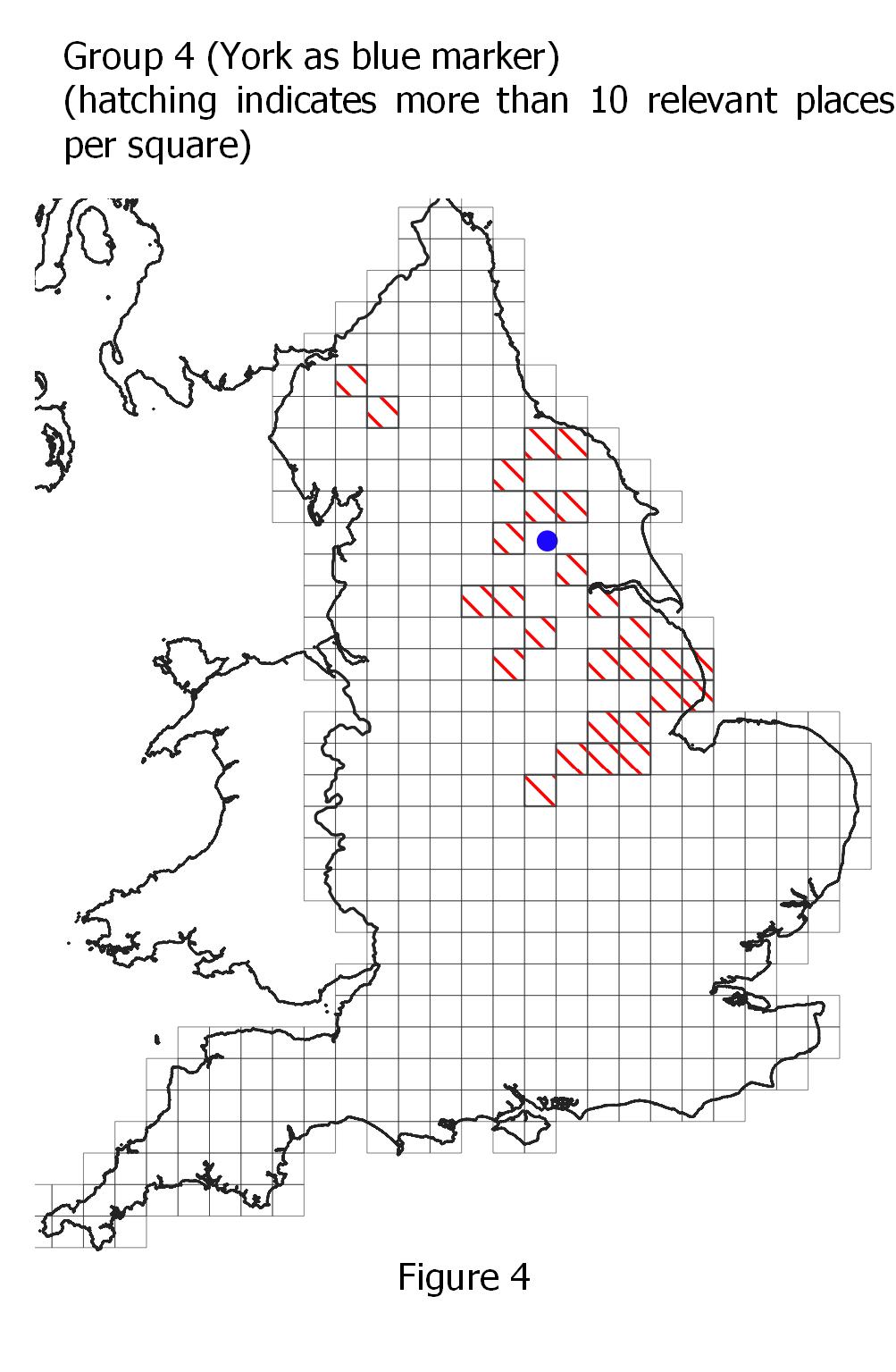

Group 4's most important elements are: "by" (n=592), "thorp" (n=287), "holm" (n=104) and "kirk" (n=80). It is only the significant presence of the place name element "by" that enables us to be relatively certain, on linguistic grounds, that this group has Scandinavian origins. Scandinavian it might be, but Viking Age it is not, at least not with any degree of certainty as the established use of bū in Anglo-Saxon literature is difficult to explain as a Viking Age introduction. It is also interesting that "thwaite" (meaning "clearing") place names do not seem to be correlated with Group 4, even in the far north-west, where Scandinavian place name elements are relatively common. "Thwaite" names are somewhat separate and predominate in and around Lakeland with some authors suggesting a Norwegian origin. However, they are also found near the Pennines and the Yorkshire Dales. This could imply a topographical effect with "thwaites" indicating the clearing of marginal lands on the hillsides.

| Name Element | Modern meaning | Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| "by" | ("settlement, village"). | "By" is generally regarded as the litmus test of Viking Age Scandinavian settlement. However, it might not be that simple. Argen Versloot (3) points to the existence of Danish relics of the word in Old Fresian (following an early Scandinavian occupation of the coastal area). This includes place names such as "Schoubu" with "bu" equivalent to modern Danish "by". Strangely bū exists in Anglo-Saxon see Sweet's Glossary entry "būn. dwelling 12 b/81,5" (14), and as b?an in Sedgefield (13) indicating its pre-Viking Age use in England (Scandinavian words are not generally believed to have entered the written language until the Middle English period (16)). I am grateful to Arthur Wright for drawing my attention to Sedgefield (13), and in particular the phrase "meduseld būan" from Beowulf. |

| "thorpe" | ("secondary settlement"). | Derived from the proto-Germanic þurpą (11) (þ is equivalent to "th"). Similar words are to be found in both West Germanic (Old Saxon and Old Fresian "thorp") and North Germanic languages (Old Norse þurpą.) |

| "holme" | ("holly, island"). | Derived from proto-Germanic hulmaz. Similar words are to be found in both West Germanic (Old Dutch "holm")(11) and North Germanic (Old Norse "holmr") (11). |

| "kirk" | ("church"). | Most Germanic languages (both North and West) pronounce the word for "church" with a hard "k", eg Old Norse "Kirkja"(7), Dutch "kerk" (7). It seems that only West Frisian "Tsjerke" (7) resembles the southern English word "church". |

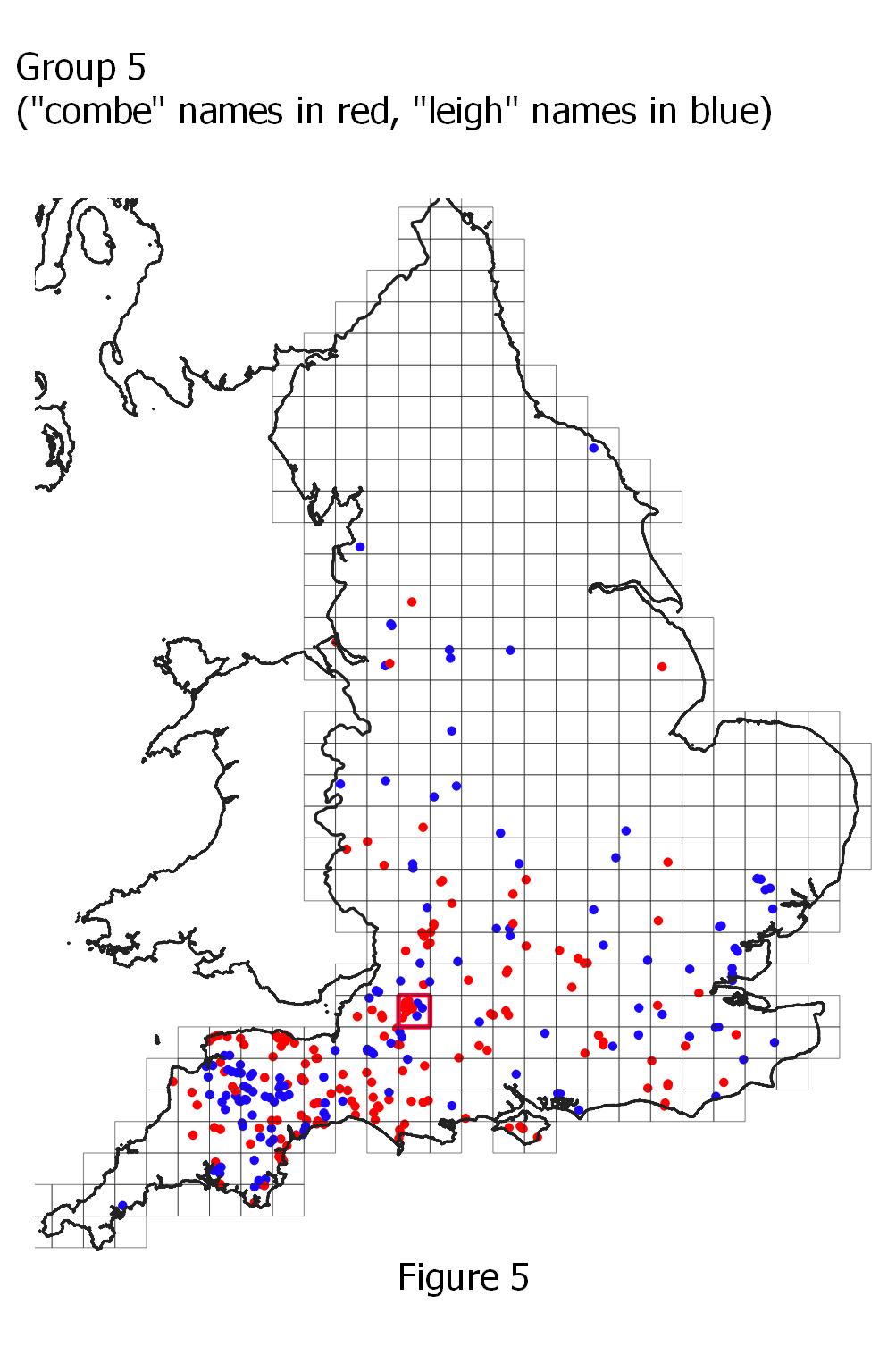

Group 5's most important elements are: "combe" (n=163) and "leigh" (n=140)

| Name Element | Modern meaning | Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| "combe" | ("valley"). | Is common in Devon and Somerset. It derives from the Celtic "cwm" (11). Interestingly it occurs with both English and Celtic word orders (specific first or generic first), as in "Monkton Combe" and "Combe Hay (both south of Bath in Somerset and only a couple of miles apart - as well as being close to the termination of the Celtic Wansdyke). |

| "leigh" | ("a woodland clearing"). | Possibly an alternative spelling of "lea" or "ley", which seem to be preferred in some places. Conventionally it is thought to be derived from the proto-Germanic lauhaz (11). Similar words are to be found in both West Germanic (Old Saxon "lōh" and Old Fresian "lāch")(11) and North Germanic languages (Old Norse "lō")(11), howeve, as above, its distribution may suggest a Celtic origin. |

Part 2

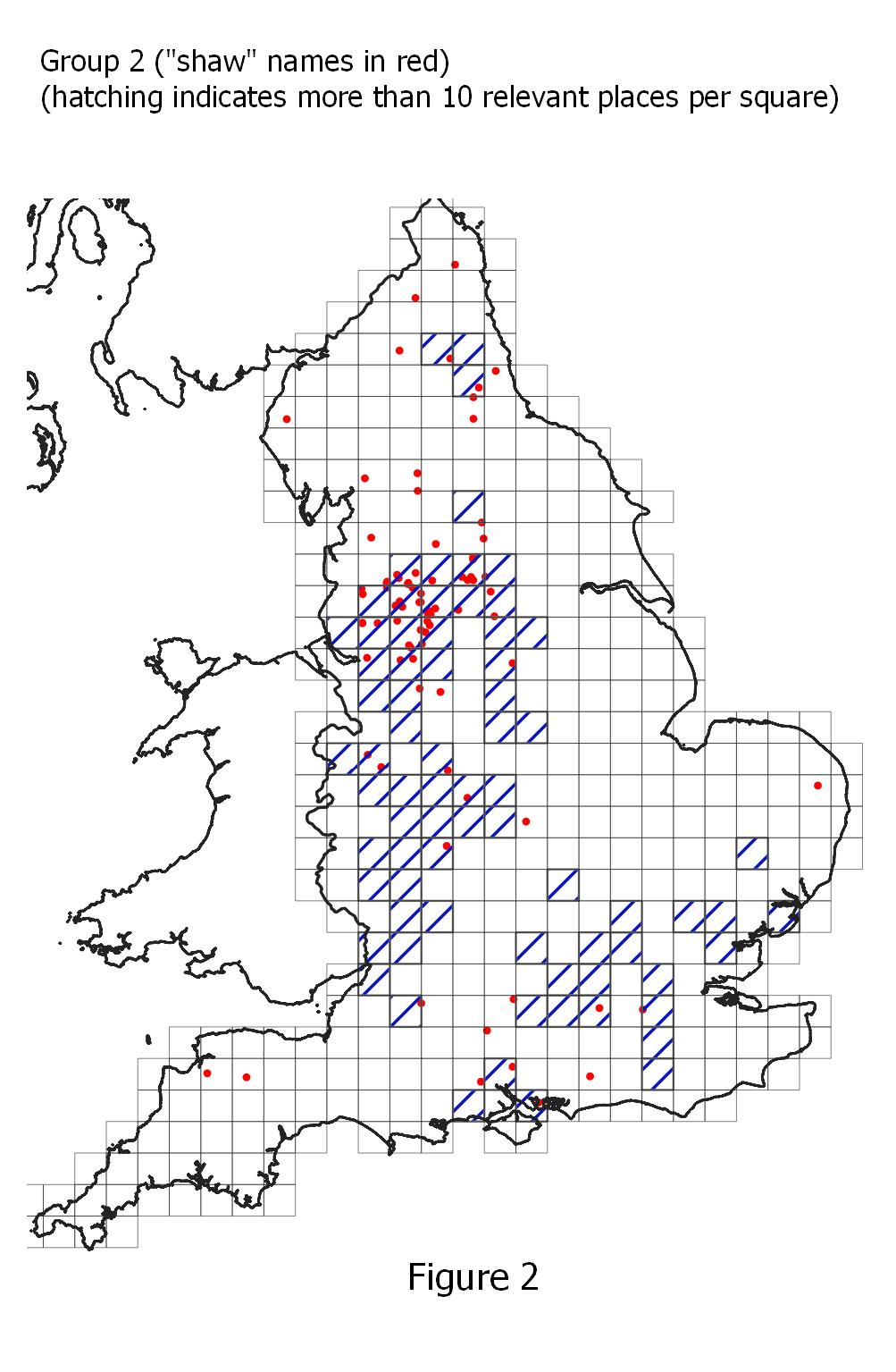

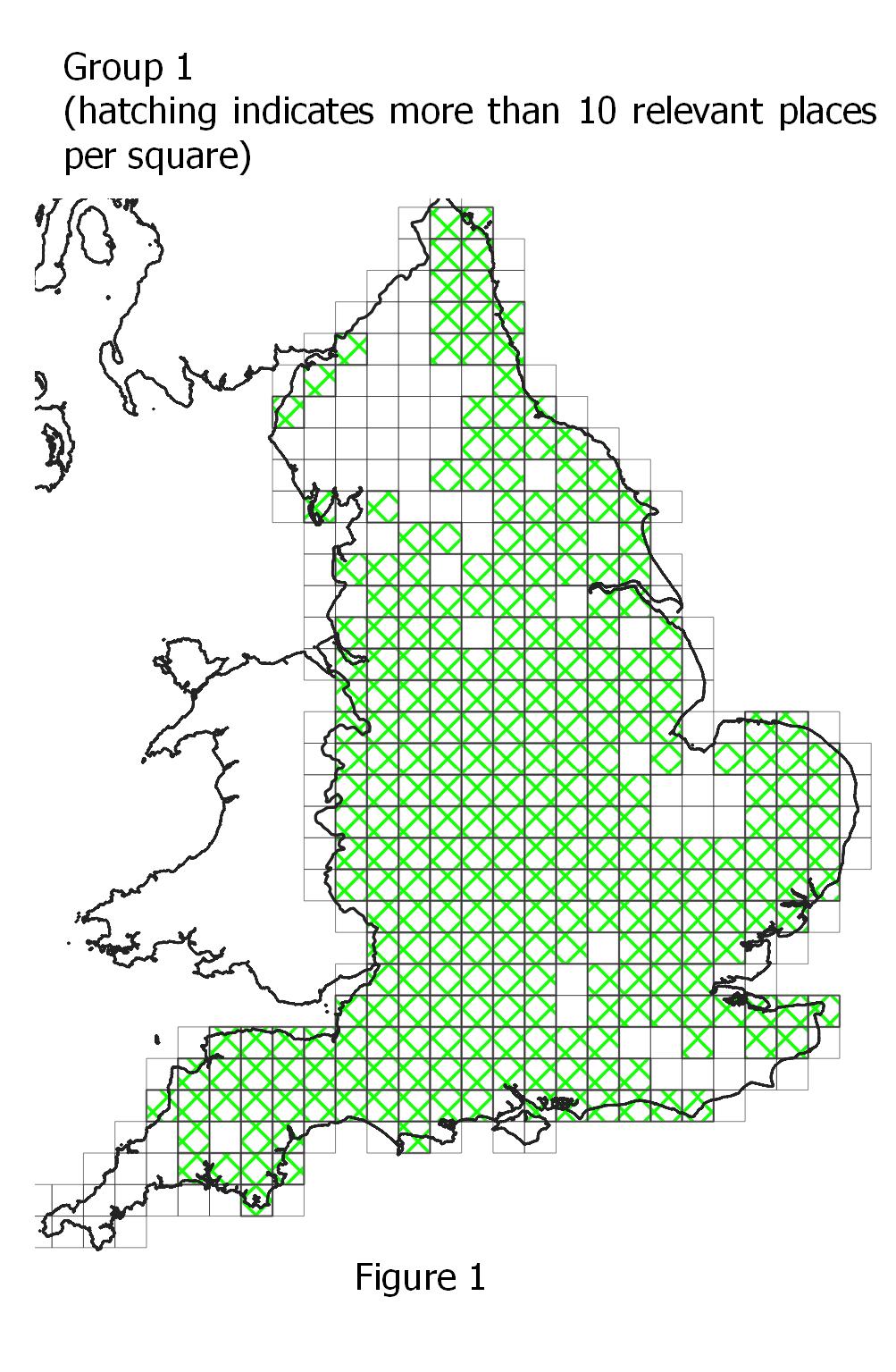

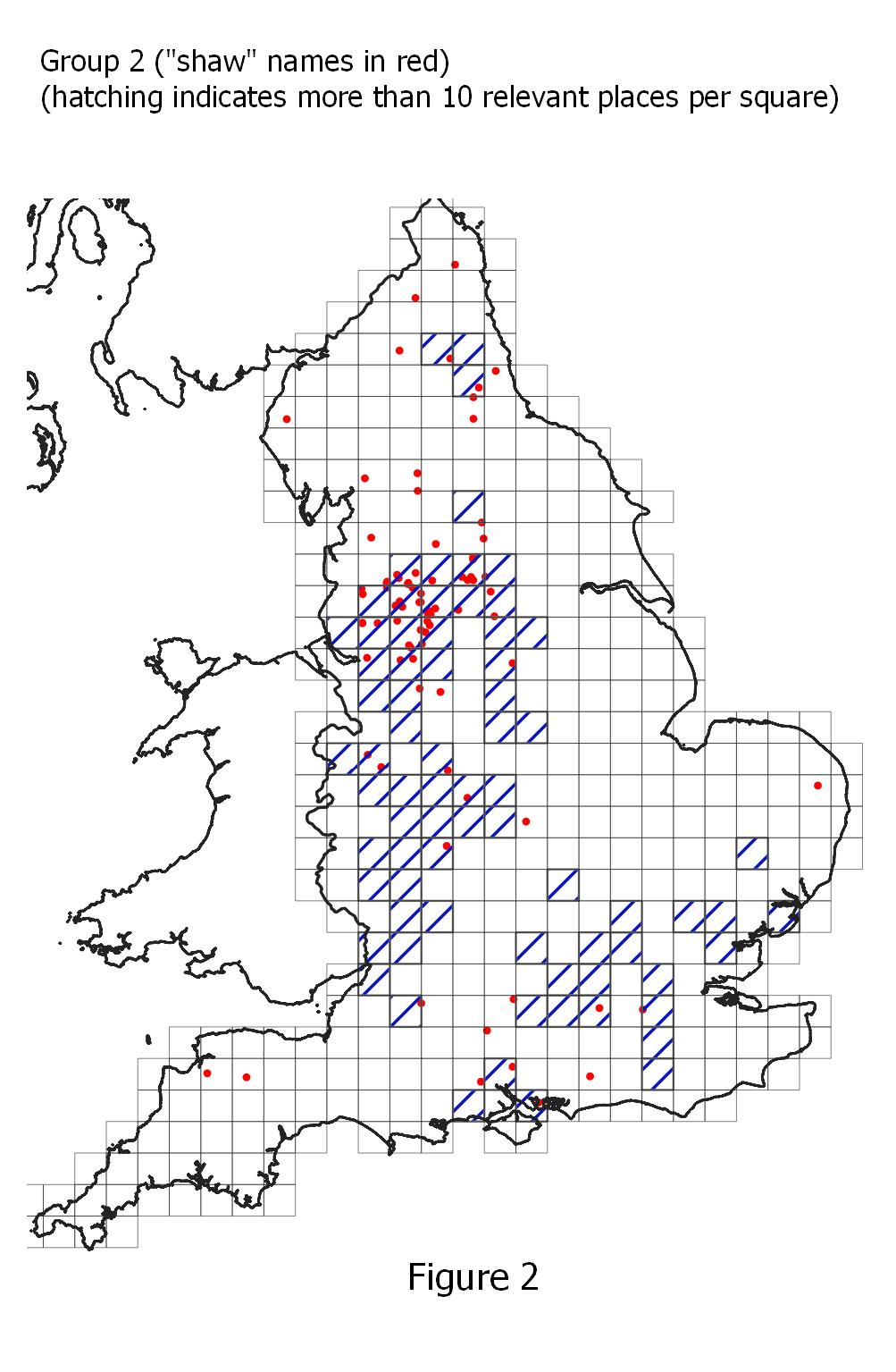

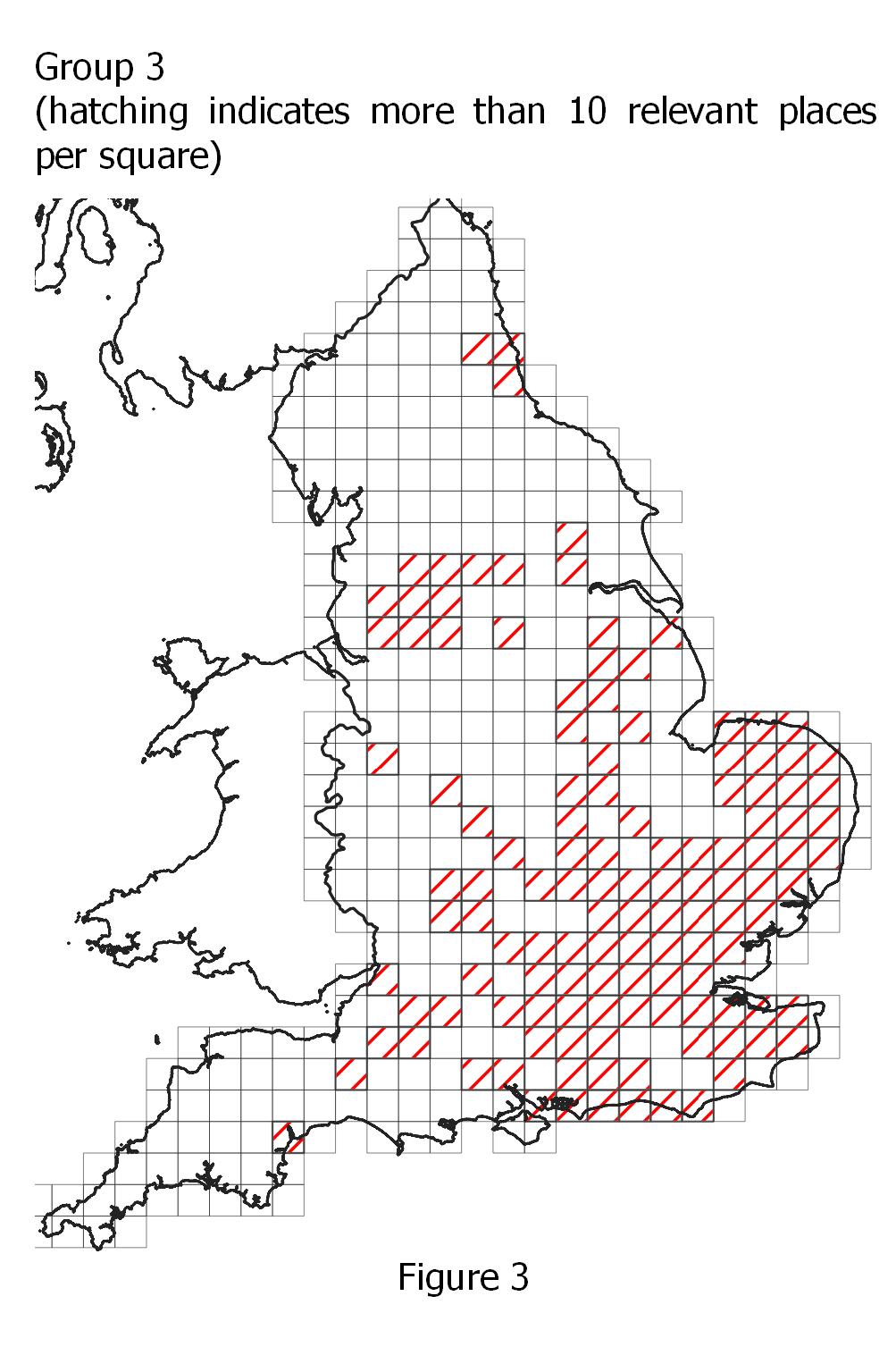

I used QGIS to map the data. My difficulty was to show sufficient information to illustrate the important points, without overwhelming the eye with too much detail. I used the squares from the factor analysis and shaded the ones in which the factor densities were relatively high (10 or more settlements per square). For example, on the map for Group 1 if there are more than 10 settlements that contain place name elements: "ing", "ford", "nor", "ton" or, "bury" within a grid square, it is cross hatched. Cross hatching in different directions and different colours enabled me to show whether the groups overlapped. Group 5 has only two place name elements of any significance which means that all places could be mapped individually. Unsurprisingly, where place name elements group together within grid squares, those grid squares themselves tend to form clusters.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of Group 1 (loading on: "ing", ford, nor, ton and bury). This grouping is present throughout most of England with the exception of: the mountainous far north-west; Fenland (serious draining did not begin until the end of the sixteenth century); the Weald; and Cornwall (still Celtic during the Anglo-Saxon period). The "centre of gravity" is quite close to Birmingham at 160 km west and 6,882 km north. Their widespread distribution may be the result of Europe wide linguistic lineages of these place name elements.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of Group 2 ("ley", "field", "ac""brad" and "shaw"). I have highlighted the "shaw" place names as the only place name element in Group 2 that seems to have unequivocally North Germanic origins. If groups imply common origins, all other place names in Group 2 would be North Germanic by association. The distribution of Group 2 is quite complex. Its core runs along the Welsh borderlands and spreads northwards through Lancashire and Yorkshire, with outposts north of the Tees as well as into the south-east (ie an area not thought to have been subject to extensive Viking Age settlement). There are relatively few in East Anglia, Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and the mountainous far north-west.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of Group 3 ("ing", "ham", "den", "stead" and "street"). The highest concentrations of Group 3 place name elements occur in East Anglia and the Home Counties including Kent, with outposts in the north-west and the far north-east. They are the only place name elements to be plentiful on the Weald.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of Group 4 ("by", "thorpe", "holm" and "kirk"). The highest concentrations occur in Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Yorkshire and the far North-west. If "by" names were brought by the Vikings, we would expect them to be common in East Yorkshire where there is some archaeological evidence of Viking activity. In fact they are less common in coastal East Yorkshire.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of Group 5 (only "combe" and "leigh"). The highest concentrations occur in Devon and Somerset. As there are not many of them, I have shown them all individually. "Combe" names are shown in red and "leigh" names in blue. It is not surprising that the British place name element "combe" is common near Bath, a walled Romano-British town near the termination of the Wansdyke.

Inevitably it was impractical to consider every place name in England individually, as a result some place name elements will have been flagged up in error. Handling error is the norm for statistical analysis, the hope is that any systematic "signal" will still be visible through the random error. Obviously "signal" can get overwhelmed by "noise". However, the mapping discussed in Part 2 provides some reassurance. If the groups were simply the result of random associations, there would be no reason to suppose that adjacent squares would be similar. In fact they frequently are. What seems reasonably certain is that Anglo-Saxon England was not a homogenous random mixture of place name types. In trying to understand the origins of the groups, I seem to have stumbled into some unexpected findings. I was particularly surprised at the doubt that etymology casts on the origins of some place name elements, particularly those I had hitherto regarded as unequivocally "Scandinavian", or "Anglo-Saxon". Linguistically, there is a lot of overlap between the two which means we have to be cautious in their interpretation. It may be that it is custom which determines which words are used in place names by particular groups, and custom can change through time. We should not assume that Viking age Scandinavians continued to use the place name element "by". We see huge numbers of "by" place names in Lincolnshire, but we must keep an open mind about whether they arrived with Viking age settlers, rather than with their Anglian predecessors. We need to be aware that these place names are rare in other Scandinavian possessions in the Viking age.

When I began I had no idea what I might find. It turns out that apart from one group of place name elements (Group 1) that are found throughout most of England, the other groups form local clusters. With Group 2, these appear at opposite ends of the country, so clusters of squares containing "ley", "field", "ac", "brad" and "shaw" appear as far apart as Sussex and Surrey on the one hand and Northumberland and Durham on the other. Similarly for Group 3, where clusters containing place name elements "ing", "ham", "den" and "street" are found in both Tyne and Weir and in Torbay. The existence of multiple clusters of a single group allows us to rule out local fashion as their cause. For, while fashion might explain a single local cluster, it is a highly improbable explanation of multiple clusters at opposite ends of the country. Group 4 place names are usually taken as markers of Scandinavian settlement. Perhaps tribal origins also account for the distribution of Groups 2 and 3. If so, Anglo-Saxon settlement was an extremely complex affair.

1. List of generic forms in place names in Ireland and the United Kingdom. [Online] 18 09 2021. [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_generic_forms_in_place_names_in_Ireland_and_the_United_Kingdom.

2. Eurogeographics. Access Data (Open Gazetteer). [Online] 2021. [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://www.mapsforeurope.org/access-data.

3. Versloot, Argen. Frisian Place Names and Place Names in Friesland. [Online] [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/1770040/135151_398073.pdf.

4. Department of Nordic Research. Common place name types. [Online] [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://names.ku.dk/place-names/common_place-name_endings/.

5. Sweet, H The Student's Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1897.

6. Bosworth, J. n Anglo-Saxon Dictionary Online. [Online] Facutly of Arts, Charles University, 2014. [Cited: 07 02 2022.] https://bosworthtoller.com/29104.

7. Glosbe. Glosbe Dictionary. [Online] [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://glosbe.com/.

8. ARCHI MAPS UK: Place-Name Meanings. [Online] ARCHI MAPS. [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://www.archiuk.com/archi/list_of_english_place_names_and_their_meanings.htm.

9. WordSense. WordSense Dictionary. [Online] Wordsense. [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://www.wordsense.eu/.

10. Etymonline. Etymonline Search. Online Etymology Dictionary. [Online] [Cited: 15 02 2022.] https://www.etymonline.com/.

11. Wiktionary. Wiktionary, the free dictionary. [Online] [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Wiktionary:Main_Page.

12. Fellowes-Jensen, G. Scandinavian settlement names in Yorkshire. Copenhagen: Copenhagen: I kommission hos Akademisk forlag, 1972.

13. Sedgefield, W.J. An Anglo-Saxon Book of Prose and Verse. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1928.

14. Sweet, H. Anglo-Saxon Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1922.

15. worden.org. Worden.org. [Online] [Cited: 20 01 2022.] https://www.woorden.org/woord/shaw.

16. Gramley, Stephan. The history of English an Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019. p. 64.

17. The Scale and Impact of Viking Age Settlement in Northumbria. eprints.whiterose.ac.uk. [Online] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/131679/1/MED37_R1.pdf.